Victor Peeters is a Dutch national who dances at the Brno-based Ondráš Military Art Ensemble, as a full-time dancer and assistant to the dance leader, a role which also involves occasionally leading rehearsals and choreography. The dancers from the company give 65-70 performances a year. Brno Daily’s Francesca Bottini and Kahlie Wray sat down with Victor to find out more about the group and how he got involved…

BD: Where are you from and how did your passion for folk dance begin?

I’m from the Netherlands, about 30 minutes from Amsterdam. I started dancing when I was 15, which is quite late – especially for those who go on to become professional dancers. Before that, I was more focused on music. As a child, I sang in various choirs, I also played trombone for about 10 years and performed in youth symphonic orchestras. It wasn’t until later that I realized how much I enjoyed dancing. My parents actually met in a folk dance group in Amsterdam—my mom was the leader of the group, and she still is today. Despite this, my parents never pushed dance onto me or my siblings. There are three of us, and two of us found our own way to dance, while the third moved to Hong Kong and plays in a symphony orchestra. So, I definitely come from a creative and artistic family.

BD: Where has your career taken you so far?

I moved from the Netherlands 10 and a half years ago on a whim, basically! I got a call from a friend who saw that there was an open spot in the Slovak State Traditional Dance Company, in Bratislava. At the time, I wasn’t a professional dancer – I was just a very enthusiastic amateur. I told my best friend about it, and he said, “This sounds like the kind of story we’ll tell our grandkids in 50 years – remember that time we went to Central Europe for a dance audition?” I thought, okay, let’s do it! So, three friends and I packed into one car and drove 12 hours for the audition. A month later, I got a call saying, “Hey, you’re accepted.” And that’s how my professional dance career began – it wasn’t something I had really planned. I always loved dancing, but I assumed I wasn’t good enough to make a career out of it. I didn’t think there was a real opportunity to earn a living from it. But I started dancing professionally in Slovakia and I lived there and danced with them for five years.

When I first joined, they made it clear: “We can’t guarantee you’ll ever perform on stage”. But then a few things happened, two senior dancers were injured almost immediately after I arrived, and suddenly they needed me to perform. That meant intense training, with people drilling me into shape, which was both challenging and incredibly helpful. After five years, I returned to the Netherlands to finish my bachelor’s degree. Then Covid hit, and I wasn’t sure what would happen to the arts and culture sector. In my mind, I had already closed the chapter on my dance career. The fact that I had danced professionally for five years was something I never imagined possible, and I felt grateful for that experience.

BD: What brought you to Brno?

While I was dancing in Bratislava, we had joint performances and programmes with the Ondráš Military Art Ensemble , which is the group I’m now part of here in Brno. I knew some of the dancers here and had heard good things about the company. My girlfriend (now fiancée!) is from Bratislava, so I knew I wanted to return to Central Europe after my bachelor’s degree. When considering my options for a Master’s degree, I made a list of pros and cons of good universities that would also allow me to continue dancing. I wanted a university within a two-hour radius of Bratislava, so I considered Vienna, Brno and Budapest. After weighing everything up, I chose Brno, mainly because of this ensemble and because Masaryk University had a strong programme in my field of study. It was the perfect combination of a good university and the opportunity to continue dancing at a high level. As I was already familiar with the company from our performances together in Bratislava, it felt like the right decision.

BD: What is the Ondráš Military Art Ensemble?

The ensemble was originally founded in 1954 by men serving their mandatory two-year military service. To bring some enjoyment and creativity into their time in the military, they started a dance group. Over the years, the ensemble grew and evolved. After the split of Czechoslovakia, the group was also divided—one part remained in Brno, while the Slovak counterpart eventually ceased to exist. Ondráš continues to honor its military origins and remains supported by the Ministry of Defence.

Its structure reflects this history, with military leadership overseeing the ensemble, while artistic direction is handled by a civilian leadership team. The artistic department includes an artistic director, a dramaturg, and leaders responsible for both the dance and music sections. The ensemble consists of different groups working together. The dance section is made up of five professional couples, meaning ten full-time dancers, who regularly perform. There is also an external dance group, sometimes referred to as amateurs, though they are paid. This group consists of 21 dancers—16 women and 13 men—who train twice a week in the evenings for about three hours. The ensemble’s performances vary in scale. Some programs are designed specifically for the professional dancers, others involve the full ensemble.

BD: From what you’ve experienced so far, is it common for a Ministry of Defence to have a permanent folk ensemble?

It used to be quite common, but not so much anymore. Many countries in Central and Eastern Europe had both a national folk ensemble and a military folk ensemble. This was largely a remnant of the communist era, where cultural institutions were closely tied to national identity and state support. In Hungary, for example, this structure definitely existed, and the same was true for Bulgaria, Russia and Poland.

The origins of these military ensembles were quite similar across the region. They often began with conscripts who wanted an activity outside of military drills, and over time, these groups became official institutions. At the same time, national ensembles were created as a way to promote cultural pride and strengthen national identity. Today, it might seem a bit unusual for a Ministry of Defence to fund a folk ensemble, but there are historical and practical reasons behind it. In fact, our own ensemble was nearly disbanded in 2008 during the financial crisis. At the time, the government was making budget cuts, and the Defence Minister considered our funding unnecessary. However, a large petition was launched, gathering thousands of signatures from people who wanted Ondráš to continue. In the end, the Defence Minister who pushed for the cuts was removed from office, and her successor allowed us to continue.

Although we primarily focus on dance and music, we also contribute to military and state events in various ways. Our musicians perform at military conferences to create a formal atmosphere, and we participate in events such as the annual Czech Army Ball, where we not only perform but also help organize the event and welcome distinguished guests, including the President. In this way, our work extends beyond just folk performances—it also plays a role in fostering a positive image of the military and making formal occasions more engaging.

BD: Are you the only foreigner in the ensemble?

Yes and no. Technically, no, because we also have Slovak dancers in the group. However, Slovaks are often seen as more of a natural fit since the Czech Republic and Slovakia share a deep cultural and historical connection. So, in that sense, they’re not really considered “foreigners.” If we look at it from the perspective of nationality, I’m the only member who is neither Czech nor Slovak. As far as I know, I might even be the only non-Czech or non-Slovak in the history of the ensemble. I’m also certainly the only dancer who has made the transition from the Bratislava-based ensemble to Ondráš in Brno. In the past, dancers have occasionally moved in the opposite direction—from Brno to Bratislava—because the Bratislava ensemble is larger, and some see it as a step up. My decision to come to Brno, as I mentioned, was based on completely different reasons.

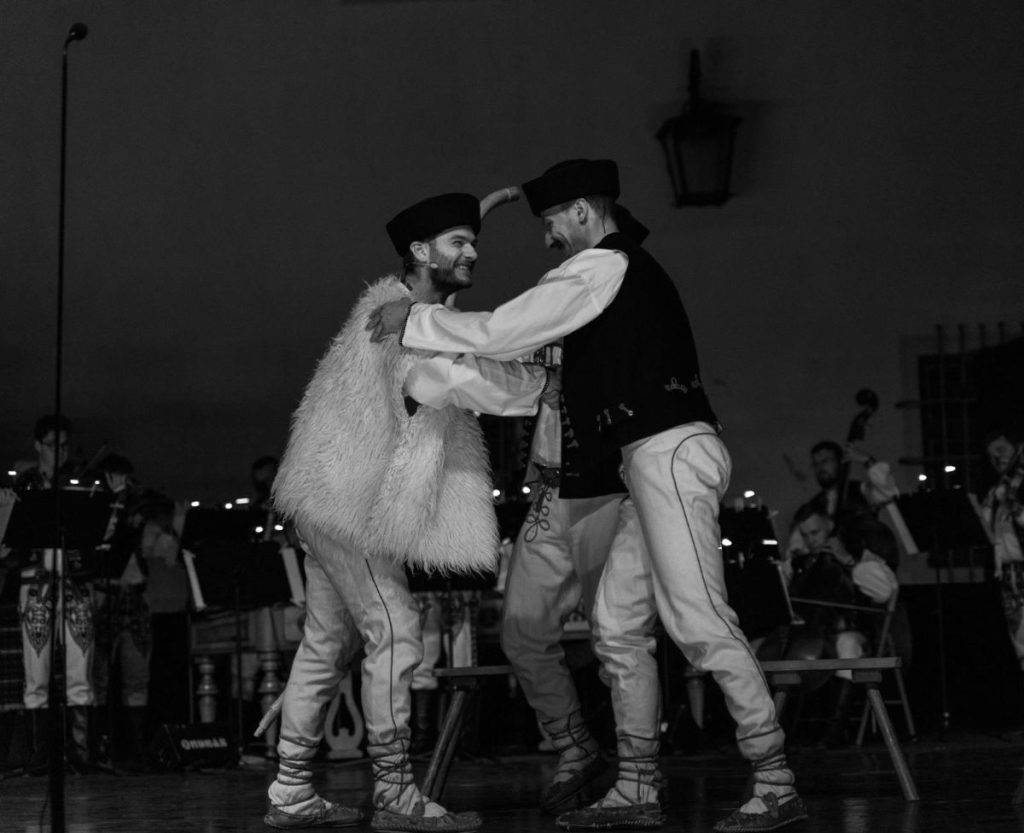

BD: What kind of attire or costumes do you wear on stage?

On stage, we wear traditional folk costumes that correspond to the specific dances we’re performing. This is something we take very seriously—each dance must be presented in the appropriate attire from its region. You wouldn’t dance a piece from one area while wearing a costume from another; everything has to be historically and culturally accurate. Ondráš has multiple types of performances. Some programs aim to present folk culture in its purest form, staying as close as possible to archival videos and traditional methods passed down through generations. In these cases, the costumes remain strictly traditional. Other programs take a more stylized approach, incorporating modern elements while still being rooted in folk traditions.

For example, a musician in the ensemble who had studied traditional albums from different regions once composed new music for the group inspired by them. When we perform these more stylised pieces, there’s a general rule in folk stage dance: the more modernised the music, the more stylisation is allowed in the choreography and costumes. So if the music has symphonic or contemporary elements, we can incorporate modern or non-traditional steps into the dance. The costumes also evolve – sometimes we wear jeans with embroidered waistcoats that maintain a geographical and cultural reference, but with a modern twist. We also have children’s performances that don’t involve folk dancing at all. For these we wear completely different costumes – like a giant robot suit or a bee costume for a show where I help teach children about kindness and good behaviour. So while our main focus is on traditional folk dance, our performances range from historical authenticity to creative adaptations, depending on the programme.

BD: What is the typical turnout for your performances?

It really varies, but we rarely perform for a small or empty crowd. For most shows, if there are 200 seats available, I’d say around 180 of them are usually filled. Some performances are even bigger—every year, we have Evenings with Ondráš at Špilberk Castle, where around 700-800 people come each night. Since it’s free (like all our performances, as we are funded by the military), it always draws a large audience. The only thing we ask is for voluntary contributions to a chosen charity fund. We also perform in major theaters, like Janáčkovo divadlo, which has about 1,000 seats. Last October, we had our anniversary concert there, and it was completely sold out. But on the other end of the spectrum, we also do smaller shows, like performances for school children, where just a few classrooms of kids might be watching. So, we dance everywhere—from small gymnasiums to grand sold-out theaters. It really depends on the type of performance and the audience.

BD: How do you typically train for performances?

We have a fairly structured training schedule. On a typical day we practice from about 9am until 3 or 4pm. Our warm-up usually lasts about an hour to an hour and a half. After the warm-up, we move on to repertoire rehearsal. Our dance leader is incredibly good at picking up on the smallest details in our dance. During rehearsals we sometimes get creative, using different dance techniques, and we often change partners, as it’s important that everyone in the group can dance with everyone else, especially in case of injury during a show. We also get about 30 minutes of individual time for personal development – working on lifts, stretches or rhythmic exercises. And of course there are some fun traditions, like when it’s someone’s birthday. The person celebrates by bringing lots of food for the group, and nobody knows exactly when this tradition started, but it’s been going on for decades. Little traditions like this are what give the ensemble its unique identity.

BD: What has been your most memorable experience with Ondráš so far?

I’ve had so many memorable moments, for example I remember my first performance very vividly. I had only been with the ensemble for about three rehearsals before they put me on stage, so that was incredibly stressful.

However, if I had to choose one performance, it would be the one we talked about earlier—the more modern program where a composer created his own music based on folk tunes. I played the main character in that show, and although the audience was small (the theater was only half full), something about that night just clicked for me. I connected so deeply with the material and the role. After the performance, I went to my dressing room and just broke down crying—tears of pure emotion. It was the most emotional performance I’ve had so far because it wasn’t just about dancing; it was about expressing a wide range of emotions. It felt more like acting than dancing, and I had to pour everything I had into that role.

For me, the best kind of performance is when I can really give my soul to the audience, even if there are mistakes in the dancing. At that moment, it’s less about perfection and more about the connection I make with the audience through my passion. That’s the feeling I strive for in every performance.

BD: Do you see yourself returning to the Netherlands?

I just got engaged in December, and we’re living together in Brno now. My fiancée recently started her residency at the neurology department, and it’s something that can’t be paused or continued somewhere else, so for the next five years, we’ll definitely be here. After that, who knows?

But I don’t feel a strong urge to return to the Netherlands. Leaving the Netherlands was a big decision, especially with family and friends being there, but what made it easier was that I didn’t feel completely at home in Dutch society. The system is so rigid, efficient, and maximized for every moment of every day, which doesn’t really suit me. I come from a creative family, and the lifestyle there just felt too structured. In the Czech Republic, people live to enjoy life, and I love that.

BD: Would you say Brno feels like home to you?

That’s a tough question. I would like to quote the Czech national anthem – “Where is my home?” – because it’s a bit like that for me. I feel at home quickly and almost anywhere. When I lived in Bratislava, I felt like that was my home. Now, I feel at home here in Brno as well. I see myself as a European, and I believe I can adapt and make any place my home. I’m not saying I’ll live here forever, though. My fiancée is from Bratislava, and while she initially felt very attached to her city, she left to be with me here. So, it’s possible that we could move back there at some point, or even back to the Netherlands, or somewhere else entirely. For now, we’ve committed to staying in Brno for the next five years, but after that, we’ll reassess and see where life takes us.