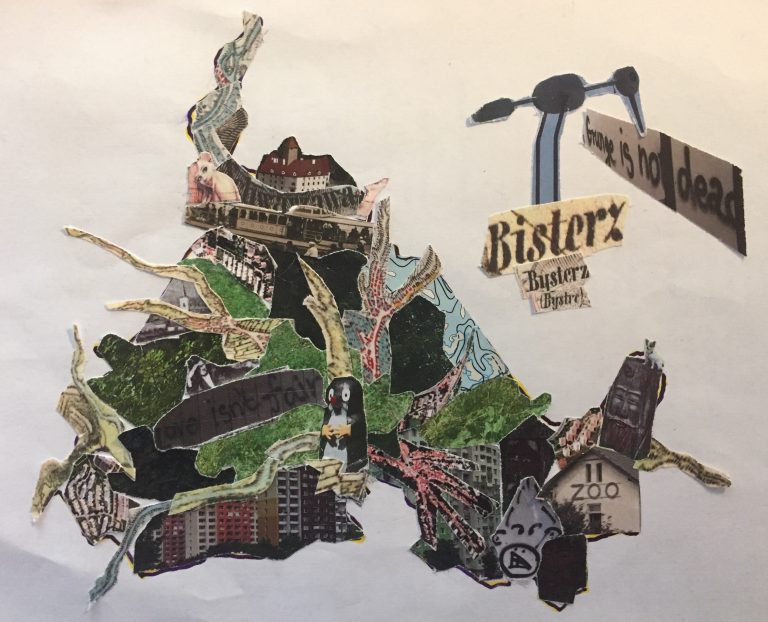

Work of art: Joe Lennon.

Part 4 – Bystrc

It’s August – summer’s zenith – the days are long and hot, and the nights are velvet. This time of year is always languidly beautiful in Brno. There’s a stunned lull in the streets. Weeds gush up through slabs in the backlots. Clouds build into Baroque postmodern piles, and from somewhere behind them there’s thunder. It might rain; it might not. If it rains, it’s a pelting torrent. If it doesn’t, the air is an amphitheater waiting for a play that never starts. You can watch it all through a wine glass to ease the tension. But either way, the drama is resolved (whether earned or unearned) in a radioactive orange sunset.

Summer is my favorite season by far, but it also freaks me out a little. I’ve always associated the summer with an over-fullness, a too-much-ness, an overabundance of rioting, squirming life. If you look at summer on the surface – say, on a short walk through the woods – it’s calm and green and pleasant. But if you turn over a rock, you see the swarming, pulsating abdomens of insects. Peer into the clotted mud of a pond and you see minnows flash as they pick clean the bones of bigger fish. Life is overactive even in your own kitchen; you reach for the bread you bought three days ago, and as you go in for a bite you see it’s wrinkled with purple-white spores. In summer it’s easy to sense how non-human life thrives in so many ways we’re not comfortable with.

I think it’s this ancient uneasiness with nature, with the uncontrolled paths it can take, that gave rise to the folk belief in all sorts of devils, demons, goblins, sprites and tricksters that populate the countryside. That’s why I also associate the summer with those supernatural creatures. The Czech lands are full of such beings – there’s one for every furrow, every pond, every bend in the road. Most of them won’t bother you if you follow the established order, give them respect, and don’t disturb nature’s balance – but if you cross them, they have horrible ways of bewitching you, leading you astray, and relieving you of your wits – or your life.

For example, there’s the vodník, notorious for luring young women into lakes and capturing people’s souls in teapots.

There’s the lešij and the hýkal, who protect the forest from poachers, but in their spare time confuse travelers with strange calls, leading them off the path into deepest woods from which there’s no escape.

There are rusalky, the lovely spirits of maidens who died before their time. They hang out by creeks and rivers, seducing men and tickling them to death with their breasts.

There’s the polednice, who materializes when the sun is high and blinding. She whips people working in the fields and turns despairing mothers into smotherers.

And this summer, there’s another demon, another scary surplus of life we don’t want, haunting the Czech lands. Its inner workings are mysterious, but its typical M.O. has become familiar. It secretly infiltrates large gatherings, flies up people’s noses, gives them coughs and fevers, takes away their smell and taste, and forces them to stay indoors for weeks. If it doesn’t put you in the hospital, it will still destroy your summer, ruining your vacation plans and leaving you moping at the window, jealous of anyone you see roaming freely outside.

This beastie’s technical name is SARS-CoV-2, but it has a couple of other cute nicknames. No matter what you call it, it sucks. And a few weeks ago, I crossed its path (or it crossed mine), and ever since I’ve been quarantined at home, feeling somewhere on the spectrum between really ill and just all out of sorts.

I won’t complain too much; I seem to have survived without the worst symptoms, and at least I’ve been able to recover at home instead of needing more urgent care. But still – it’s been a huge bummer to be stuck indoors while the best of this bright, voluptuous summer slips by.

On one of my leaden afternoons trapped at home, I had a woozy vision (possibly fever-induced) in which I encountered a heretofore-unknown local demon. He jumped out at me at some godforsaken crossroads strewn with the bones of pedestrians (I think it was Veveří and Žerotínovo náměstí), and transfixed me with a fiendish stare. He said, “You’re now cursed, in a weirdly specific way! You must spend the rest of your days in ONE cadastral district of Brno. You can choose which one, but choose wisely – for you can never leave that neighborhood as long as you may draw breath! Now choose quickly – you have only as long as the ‘walk’ light is green to speak the name.”

Since I had only 1.25 milliseconds, I made a quick calculation, and chose…Bystrc.

“Okay…um…sure…great choice, cool!” said the demon. Then there was a long, awkward pause before he said, “What – did you expect me to magically shazam you all the way out there? Come on, you can take the trojka. You have a šalinkarta, I assume? Ok, they’re doing roadwork at Grohova though, so you’ll have to walk up to Konečného to catch the tram. Šup šup. Mějte se, čau.”

Some of you may be questioning my imaginary choice to spend the rest of my life in Bystrc. But I stand by it.

First of all, it’s a wise move, statistically. Bystrc is by far the largest katastrální území in area – it’s almost twice the size of the second-largest, Líšeň. But more importantly, within that large area, Bystrc has a bit of everything. It contains pretty much every possible Brno ecosystem; not only the obvious ones – the old village-y area with winding back lanes, and the concrete swath of paneláky – but also some landscapes you can find only in Bystrc: a sparkling reservoir for swimming and sailing; a proper, fairy-tale castle (yeah, sorry, but I don’t think Špilberk really counts in that department); a deep forest where you can walk for hours without seeing anyone; and even a detention center for depressed polar bears. Maybe the only Brno thing Bystrc doesn’t have is a hipster barber shop – but if there isn’t one yet, I’m sure it’s coming soon. So, all in all, I think I could make peace with having to spend the remainder of my days in the varied nooks and crannies of Bystrc better than I could in any other single neighborhood of Brno.

I hope none of you actually meet this only-one-Brno-neighborhood-quarantine-for-life demon. Actually I’m sure you won’t, because unlike the other real demons, he’s a product of my imagination. But if your more ambitious summer plans have been derailed, and you’re looking for local adventure, you could do much worse than spend a few hours visiting some of Bystrc’s lesser-known corners.

I’ve disembarked the tram at Zoo or at Přístaviště probably 50 times in my Brno years – but until recently, I had always gone to the right and walked directly from the tram to the zoo, or to the harbor. But if you turn left at either stop, you’ll find yourself walking in toward the old, original village of Bystrc. If you push on past the first few cross streets, the hubbub of the tram stop areas disappears, and a lovely, lazy rural vibe takes over. The first mention of the village of Bystrc is in a document from 1373 – and when you’re in the middle of the quiet old town with its twisting capillaries of small lanes, you are free to imagine that little has changed since then.

I especially recommend walking down into the village from Přístaviště. You may be tempted to follow the crowds and walk the other way instead, down to the harbor – and yeah, that’s certainly fun too. I love the ridiculous strip of carnival rides, beer gardens, and langoš stands that leads down to the docks. I grew up in the southern US, so for me there’s a bit of nostalgia in running this greasy gauntlet. There’s a part of the Florida Gulf coast where my family sometimes went on vacation that’s called the Redneck Riviera. Přístaviště is about as close as Brno gets to that charming part of the planet. When I was there several weeks ago, within 5 minutes I witnessed two separate, unrelated incidents of a shirtless man holding a beer in one hand and a dripping ice cream cone in the other. Ah…my childhood.

But if you head the opposite way along Přístavní street, you’ll cut steeply down into the heart of the old village, and at the bottom of the street you’ll see a lovely little plaza with a gigantic linden tree shimmering over it. In the rich shade of the tree is a gurgling fountain and a circle of picnic tables. You can plop yourself down there and sip a cold Kozel or Radegast from Krčma pod lípou, and let the South Moravian village authenticity wash over you for a while. I found this place by accident, and only later did I read that the linden is probably the oldest tree in Brno. It’s called the Lípa u Šťávů (or just the Bystřická lípa) and it’s been alive for about 400 years. The village folk used to assemble under it for meetings and celebrations. Its center is hollow, but it still bears fruit.

In a way, the tangled outgrowth of the Lípa u Šťávů is a kind of metaphor for the development of Bystrc itself. As Brno’s population pushed out into the suburbs in the 1970s and 80s, the old village did not escape the concrete fate that swept the nation at the time. But Bystrc’s socialist makeover seems slightly less heartbreaking than the one I described in the Bohunice article – because instead of utterly demolishing the old town center as they did in Bohunice, the city planners spared it, and built the new housing estates in vast terraces on the hills above the village.

As I said in that previous article, I have a weird fondness for these panel housing estates – there’s a beautiful geometry in the pastel mazes of buildings, and when I look at them from a distance, across Brno’s hills, I get sublime satisfaction in the contrast between the blocky monoliths and the lush green slopes they float on. But regardless of my own quirky aesthetic sense, Brno’s suburbs genuinely seem like a nice place to live. Tucked between Bystrc’s paneláky there are lovely, brambly little herb gardens, and lots of open lawns with benches. As I walked through the nice part of the neighborhood above Obchodní centrum Max, I saw groups of children playing, parents chatting, and old folks watching and smiling (well, half-smiling, anyway – which I think is full-smiling for that generation).

But Bystrc’s sídliště is not all sweet suburban reverie; if you walk down Černého street, you can visit a socialist relic that didn’t manage to survive the switch to the free market – the decaying, decrepit Letná shopping center. The last shops in the building closed around the year 2000, and since then it’s been a home for squatters, a test area for pyros, and a prime makeout spot for teenagers (I actually came upon a kissing couple when I was there – but don’t worry, dear reader – their romance continued unabated). It’s probably illegal to go inside the building – so to be clear, I’m not suggesting you do it – but FYI, there is a huge gap in the half-ass fencing around it, and you can just stroll right in the main entrance. So if you’re up for a spot of mild urban exploration but you don’t want the hassle of actually breaking and entering, it may be your thing.

As I was taking pictures outside, an older gentleman laughed behind me and said, “Pan fotí privatizační kulturu” – a gentle reminder that there’s still some righteous bitterness at the way that places like this, and the people and the neighborhoods around them, fell victim to “privatization culture” – greedy owners and investors that took advantage of, and mismanaged, the public infrastructure that was (maybe cynically) meant to be “the people’s.” Maybe Letná will eventually be renovated and revived, as Bystrc’s other big socialist-era shopping centers, Max and Javor, have been. But in the meantime, its moldy terrace offers a nice view over the sprawl.

Of course, in the end, if the all-too-human cityscape is bumming you out, if the stress of this viral spring and summer has made you want to turn your back on civilization (or its imminent decay), if you want to escape the coughing crowds and take a long moment for yourself – then you can do that in Bystrc too. The vast majority of the district belongs to the Podkomorské lesy forest reserve – and there are miles and miles of crisscrossing paths, so you can plan a long hike through spruce and birch woods, and along murmuring creeks. If you want to avoid people, and more importantly, if you want to avoid the annoying drone of motorcycles coming from the Masaryk circuit – go on a weekday when there isn’t a race on.

And deep in the woods, enjoy what will remain of this teeming, heedless summer.

But watch out for ticks. And mosquitoes. And the hýkal. Dej si pozor na les.

Disclaimer: Opinions and views expressed in the text above are of the author. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.