Milan Šimánek started working at Kino Art in September 2012 as head projectionist, and became the manager of the cinema at the beginning of 2017. In this role, he is also the director of the BRNO16 International Film Festival, one of the oldest film festivals in the Czech Republic, in its 65th year this year.

Unlike most film festivals, which are run independently in partnership with the host cinemas, BRNO16 is an inside job, organised in-house by the team at Kino Art. So while directing a festival doesn’t usually come with the job of a cinema manager, Šimánek is now in charge of BRNO16 for the 8th year. Brno Daily spoke with him to find out more about preparations for the festival, which kicks off on Wednesday.

BD: Could you tell us something about the history of Kino Art?

Sure! Firstly, we’re not really sure when this building was built, because there are no historical pictures of old Art. We’ve got one picture from the 1910s of the building next door, which doesn’t look so old, but I believe it was built just before World War I, like the rest of the buildings on this street. This building housed a German youth association, and in the picture you can see into the space which is now the large screening hall, which had a decorative facade, and was probably either the dorm or some kind of gym for the youth.

It was the youth organisation which opened the cinema in 1919. Back then it started as a German-language cinema, and also educational. During the 1930s there was much pressure to make it less German, because the First Czechoslovak Republic wasn’t so open to minorities, of course, and even then it was slowly becoming more and more of an arthouse cinema. Yet there are no old pictures of this cinema from 1919, and nothing later. The oldest pictures I’ve ever found are from the 2010s, when the whole cinema complex was already built. So we guess from the socialist functionalist style that the rest of the building was built maybe in the 1960s, next to the old gym. You can still really see the difference in the walls and the ceilings; for example, in the ticket office, you can still see the historical ceiling, because it’s part of the older building, while in the cafe you can see this “commo-functionalism” style, which is now being torn down everywhere. So the cinema is old but the building is not historical.

BD: BRNO16 is coming up this week. Can you tell us about the history of the festival? How did it start?

It was founded in 1960. At that time in Czechoslovakia there was a huge movement of amateur film-making clubs, as in people who didn’t have any professional training. That’s not so weird, because FAMU, the first film school in the country, was founded in 1946, so 1960 was when only the second generation of professional film-makers were emerging, so it wasn’t such an issue if someone was just an amateur. [Martin] Frič and [Otakar] Vávra, they were all amateurs.

But also, in Brno we are close to Přerov, which was home to Meopta, a company which was building the 8 and 16 mm cameras used by amateur filmmakers to make home videos, or make videos for companies. Because the factory was so close, that meant it was possible to get the equipment. During socialism, there was usually a problem to get stuff, you could wait years and years for anything, but here we were lucky, because it was accessible.

So the festival was founded especially for those film-makers who were making videos for their companies, for their factories. In fact, in the first year there were two main prizes, one for the best movie, and one for, let’s say, the best propaganda video, which were known as agitka. You would call it a PR video now, it’s not so different from the videos that companies or corporations make now to say how well they are doing. Back then it was of course political, because the success of the company was always also the success of the socialist regime, so they were called agitka because they were used for agitation, spreading the good news.

BD: How did the festival develop?

BRNO16 didn’t start as an international festival per se, it became an international festival after three years of its existence, and then it started to open more and more. Starting from the 1980s it opened more towards professional film-makers, and back then it was a big deal for the festival, whether that was fair.

Another important issue was that these competitions, in everything, were usually organised in stages, so you have the municipal round, the regional round, the state round, and when you’ve got a good enough position in the state round, you can go to some international competitions. But because you have to go through many rounds, it means everything which is problematic is set aside, whether that means politically or speaking about movie taste. So it was usually just those “grey mice” which made it through, the least offensive films which nobody has an issue with, but it’s never the best movie, kind of like the Oscars.

BD: But BRNO16 didn’t work like that?

No, BRNO16 was built such that it was an international competition basically immediately, because of one of the co-founders, [Miloš] Nováček, who was the director of the festival for 30 years.

BD: Did he work at KIno Art?

No, he worked for one of the many predecessors of what is currently TIC Brno, from the 1950s, called Park kultury a oddechu (‘Park of Culture and Relaxation’). It was basically this umbrella organisation for municipal events and so on, basically like now, organising Brno Christmas and so on, the cultural department of the city. So the festival was founded by people working for this municipal cultural organisation, even back then, and the current organisation running BRNO16 is basically still the same company. And it’s very interesting that the festival survived the 1960s, 1970s normalisation, which as an international competition was very hard, but BRNO16 managed to run every year, including 1968. I don’t know how he did it, by some very weird survival skills. A very well connected guy, I guess.

BD: Regarding this year’s festival, what is the dramaturgical concept, or the theme?

The competition, both the international and Czechoslovak competitions, is never bent by the theme of the current edition, it’s just the best movies we selected, or the most interesting movies.

BD: So any genre, any theme, any type…?

Yes. The thing is that we are trying to make it less obvious, to think about the audience, trying to prioritise genre movies over non-genre movies, trying to avoid repetitiveness, because when you see thousands of short movies, as we do, they start to look the same. So we try to make it interesting, but that’s just, let’s hope, our good programming. But the other events are guided by the theme of this year, which is “SomeBODY to love”.

The ‘body’ is in capitals, because the theme is very corporal, very body-oriented, relating to body positivity, consent, feminism, queerness. These themes are very connected with both Kino Art and BRNO16, but are also very current and hot topics. In particular, we are trying to make it corporal because we believe this is still a big issue in current cinema. For example, we will have a workshop with an intimacy coordinator; this is a position we would have laughed about 10 years ago, and now it’s actually being taken seriously… and not just in movies, but even now in video games, for cutscenes. Baldur’s Gate 3, for example, had an intimacy coordinator. And it makes sense, because it’s being played by 12-year-old kids, and so you don’t want it to be rapey.

Another part of it will be a discussion and screenings of ethical porn, another thing which would have probably been considered a joke 10 years ago, now again a very important issue, I would say even a health issue, as a lot of kids are watching it, and you don’t want them to bring those problems home. And the whole idea for the theme actually started with another program which will be part of the festival, which is ‘post-porn’. I came across this phenomenon for the first time last year at Beast IFF, a festival of Eastern European cinema in Porto, one of our partner cinemas, and it basically means movies which use the language of pornography to express other issues. So the movies may or may not themselves be pornographic, they are often not explicit at all, they are often animated, often very abstract. But they use the language of pornography to talk about other things, often oriented towards body positivity, fatphobia, queer issues, feminism, or eating disorders.

BD: When you say the language of pornography, what does that mean exactly?

The form, basically. You are using things usually connected with pornography as a genre. It could be anything, like how the scenes are done, how the porn is cut, you can use the expressions, you can use the cliches and stereotypes. Basically taking pornography and moving it something onward, playing with it, and changing the meaning.

BD: What are you most looking forward to from this week’s program?

Of course both the international and Czechoslovak competitions are very interesting. This year’s main competition I would say is quite good, better than last year, maybe even better than two years ago. We’ve got really good movies. I am quite excited about the intimacy coordinator workshop by Virginija Vareikyte, I would say it’s a very exclusive and unseen issue here. Even though Czech cinema is very much opening up to these kinds of issues, and in the mainstream cinemas we are playing more and more movies which touch on intimacy or even pornography, still this is something which is not being used in Czech movies, TV shows, or video games, and I believe it will be very interesting and probably very mind-opening for many people.

I’m also really looking forward to the Friday ethical porn discussion, moderated by Katerina Olivova, a teacher, performer, and body design artist. She was studying body design here at FAVU, and currently she’s teaching at AMU [Prague Academy of Performing Arts]. She’s one of the most interesting current artists working with her body, in fact I believe she actually invented post-porn like 15 years ago, before anyone was thinking about it. She is post-porn, basically, through her own appeal and art, and she’s bringing the discussion and screenings of ethical porn, which will be local, from Prague and Brno. Again I believe it might be very mind-opening.

I’m definitely looking forward to the post-porn program; it will be played twice, once Wednesday, once Friday, so you can have a chance to see it again. And on Monday, there will be a much smaller event, a warm-up, in the small screening room. It’s a documentary about a stripper, which will actually be screened in the presence of both the director and the main character, so something which we didn’t even plan for so hard, and then suddenly the team is here. So there are already movies about the issues we were aiming for.

We also have a very interesting video gaming program again, it will be a presentation showing things like dating simulators, a very niche thing within video games, very connected with those issues. There will be an erotic video-game quiz, and a masterclass about erotics in video games, and for people who want to be mainstream, there will be Oscar-nominated shorts. So it’s huge, it’s big. We’ve even got a children’s program this year. Not porn oriented! But still interesting!

BD: I’m guessing you watched hundreds of short films when you were deciding on the selection…

Too many.

BD: In that case, what are the trends in short film production these days?

There are bad trends that we are trying to avoid, so it’s quite possible you won’t see those… because if you’ve seen a lot of short movies, or been to many short film festivals, you are already expecting some very cliched motifs. We try to avoid those, so actually we are hoping those movies won’t show so many trends.

In general, short movies are often made by young people, they are made by students, or people at the start of their careers, so they often tend to be quite young, quite fresh. Not always about young people, but usually not as heavy-handed as some arthouse movies can be. So we are trying to aim for these, because we like the freshness. Another thing that’s very interesting is the way bigger portion of female film-makers than in a normal movie program. I would say we are probably even around 50-50. So, then it’s interesting, why do they disappear then? Because in short movies there are a lot of female film-makers, but in full-length movies there aren’t, they’re gone. Maybe we’re somehow getting there, but it’s also quite an important trend. And you can tell these films were made by a woman, it kind of shows, so again it’s about showing a more interesting perspective than established arthouse cinema.

Many of the movies do have a kind of arthouse vibe, but it’s often broken up. We purposefully selected several movies that I would call cheesy, but still interesting and good, to break the stereotypes. We are also always trying to get as many genre movies and comedies as we can, so it doesn’t get samey and boring. We show the films in one-hour blocks, and we always try to make every block balanced. I think this is also a good thing that none of the festivals I’ve been to are doing; they are showing short movies, but one block could be an hour and a half or two hours. What’s the point? It’s a short movie festival, and you are spending two hours in the screening hall watching short movies. It’s an oxymoron. So when we are producing a short film festival, all the programs are short. In one hour you see 3-5 movies, always different moods, speeds, tempo of the movie, country of origin, we try to mix it. They are always somehow connected by some theme, but we don’t name them – they are named very boringly, Block 1 to Block 9, no clues. It’s up to every viewer to find connections for themselves, we don’t treat our viewers as schoolchildren…

BD: Finally, what does the future hold for BRNO16?

Well, it’s always a question of money, and it’s also a question if we will have visitors this year. We were not very satisfied last year. It was never really an issue with our festival, that we would be complaining there were not enough visitors, but last year we very much hit the mid-flu season, so we are hoping it will be better this year.

But next year, if everything is ok, we will be preparing the 66th BRNO16. It’s very obvious that it will be the 666 edition, so we are trying to own some kind of satanist edition, but I’m telling you right now that we are not going occult or anything, because why? We don’t know about this, we are not trying to go in for something we don’t know, and which is too gimmicky. So we’ll try to find some way to show that satanism is something which is historically taboo for some and very liberating for others. We’ve already got a headliner for that edition, which is short movies by Kenneth Anger. He is the movie maker when it comes to short movies, and very much connected to the theme of satanism. Also, his movies are wonderful, they are super brat, super queer, and actually one of his most famous movies has an original soundtrack from Janacek, so it will be absolutely hilarious. I’m really looking forward to it.

——————————————————————————————–

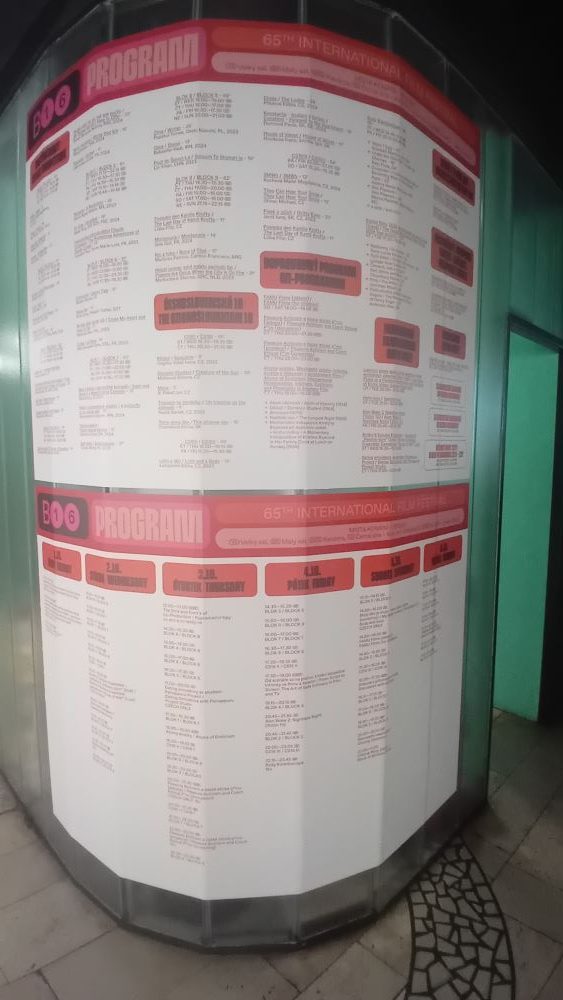

BRNO16 runs from 2-6 October. All the films in the competition program will be English-friendly, as well as most of the accompanying program, though some Q&As may be in Czech. The video gaming program may not be fully English-friendly, but can be enjoyed without subtitles.