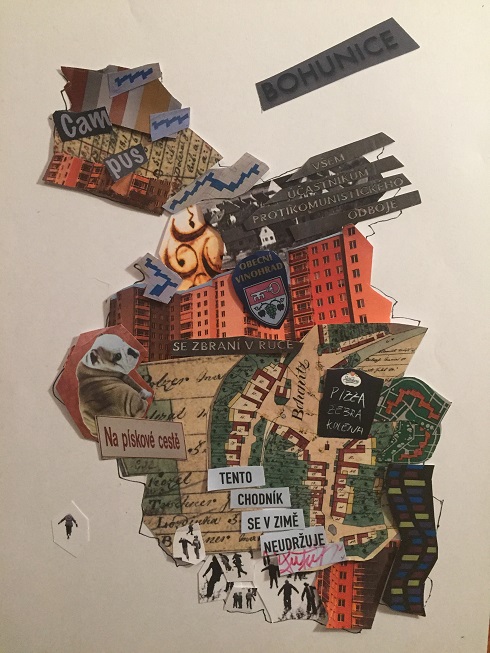

Work of art: Joe Lennon.

Part 1 – Bohunice

As fate, as love, or as the alphabet would have it, Bohunice comes first in my journey through the 48 neighborhoods of Brno. This is wonderful to me, for a few reasons.

The first reason is that it’s a part of the city almost all of you will be familiar with – mostly because it’s home to the Campus, that shining city on a hill where the professional class of Brno – university students, doctors, office workers, and academics – myself among them – come every day to sit in front of computer screens at our desks (or perhaps to lounge behind computer screens in our relax-zone ergonomic-work-hammocks). And when we are not in front of a screen, we are walking quickly to get some Starbucks or Kofi-Kofi, or to grab some Indian food or a Whopper at the food court. Or to buy a new phone. Or to buy a new coat. Or to buy—almost anything.

Because the Campus is cleverly designed so that at its center, instead of a park or a square, there’s a parking lot, and the only way to get from one side of it to the other is to walk through what’s essentially a long outdoor shopping mall. It’s the ideal neighborhood of the future—as imagined in the early 2000s, when it was being designed and built. Its stylish, swirling design creates a feeling of openness and freedom – while at the same time directing our every movement, keeping our eyes on brand names and keeping our feet turning back again down the same store-lined paths.

In many ways, the Campus is an ideal expression of the dream of global capitalism that, since the end of the Cold War, we have all been telling ourselves that we share. It’s a dream that promises peace and prosperity for everyone, and a borderless world where everyone is able to reach their potential through unrestricted creativity and technology. All this can be ours – as long as the same freedoms given to people and ideas are also given to money, and to the corporations that represent that money. Strolling through Campus, you can feel the genuine force and beauty of this globalist dream made real. In five minutes, you’ll hear ten different languages spoken, and you’ll see all colors and styles of people, mingling and laughing (and smoking) together. And you’ll see the cars and smart clothes and full shopping bags that tell of a rising prosperity among Brno citizens. And also, thanks to this dream, you’ll see me – because I never would have ended up in Brno if this new world order hadn’t prevailed in my lifetime. In and of themselves, all these are good things, and they were undeniably gained through the shared world-dream of capitalism.

And yet there’s a shadow side, a dark uneasiness, to the dream, which more and more people seem to be feeling these days. And that brings me to the second reason I find Bohunice fascinating. Because there’s another side to Bohunice too, downhill from the Campus, and it’s also the expression of a very powerful, beautiful world-dream – although one that has fallen out of power, and out of fashion – at least for now.

You can feel how much of a self-contained bubble Campus is, and how segregated it is from the rest of Bohunice, if you try to walk south from Campus Square toward the older sections of the neighborhood. You have to trudge up a muddy track, then either make a dash across the Jihlavská highway, or walk several minutes beside loud, zooming traffic until you reach the nearest crosswalk. The city has started building a new tram line that will whisk us through a tunnel underneath this no man’s land. But in the meantime, if you do decide to make the journey on foot, you might notice something interesting – a flat diamond slab of concrete which could be easily mistaken for a sewer drain, except that it usually has some flowers and red candles on top.

It’s a monument marking the spot where Josef Žemlička, a 16-year-old boy from a nearby village, was killed on August 21, 1968, as Russian troops were moving to secure the city the day after leading their invasion of Czechoslovakia. A soldier who was guarding the highway thoughtlessly fired a warning volley from his machine gun toward a crowd of onlookers, and Žemlička was hit twice in the chest. For his family and other Brno citizens, it must have been horrible to have to accept such casual cruelty, knowing there wouldn’t be real justice for Žemlička or for many others who met similar fates as long as their country was under occupation.

Unfortunately, that occupation helped support a totalitarian Czech regime which lasted another 20 years, so it wasn’t until 1991 that the monument to Žemlička could be placed here. And during those 20 years, the landscape of Bohunice was dramatically altered.

From the first mention of a settlement here in 1237, up until the mid-1970s, Bohunice (written variously over the centuries as Bounici, Ponici, Pohnycz, Bohaunicz, Bohoňov, Bohonitz, and Bohunitz) hadn’t changed all that much. It was a tiny cluster of houses cascading down the hill, surrounded by fields and vineyards – and it stayed that way for seven hundred years. Even when it was officially incorporated into the city of Brno in 1919, it was still just a village. You can see some amazing photos of the old village square here and here.

Some big changes started in the 1950s, after the Communist coup, when the small family farms in the area started being consolidated into large agricultural co-ops. The last remaining private farms were confiscated in 1962. But at that time, there were still only about 2000 people living here.

And then, in the 1970s, after centuries as a quiet little village, Bohunice was transformed into a massive, muddy construction site. Huge projects got underway on either side of the old settlement – the new hospital complex at the top of the hill, and the D1 motorway at the bottom. And in between, the authorities decided to build the ideal neighborhood of the future. They called it the Sídliště československo-sovětského přátelství – the Housing Estate of Czechoslovak-Soviet Friendship. Construction began in 1973, and over the next decade a labyrinth of grey concrete panel buildings (paneláky) shot up beside the old houses, along streets named for various republics of the Soviet Union (like Ukrajinská and Moldavská). Amid the dust and noise of the construction, roads became rows of potholes, and sewers overflowed.

The death blow to old Bohunice was delivered in 1977. Residents were called to a meeting where they learned that their family houses would be demolished and replaced by roads, viaducts, tram lines, and of course, paneláky. Antonín Crha, the current mayor of Bohunice (and quite the local historian), gives a depressing account of this meeting on the official city district website: “The family homes at these addresses were to be liquidated: Spodní 2, 6, 8, 10, Morávkovo náměstí 1 – 19, Malá 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, Vyhlídalova 3 – 6, 8, 10, Rybníčkova 1 – 7, Lány 1, Podsedky 1, 2, 4, 6, Neužilova 2, 4, 6, 8, Hraničky 25, 27, 29, 31, 33, 35, 37, Havelkova 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21. The mood was very agitated. No wonder – it was a huge intervention in the life of the original inhabitants. The entire historical core of Bohunice was to be destroyed…” (my translation). Obviously, I don’t know exactly what it was like to live in Bohunice during that time, but my imagination is helped by Věra Chytilová’s shocking and hilarious 1979 film Panelstory, which depicts the chaos in a similar sídliště under constructionin Prague.

Of course, Bohunice wasn’t alone – almost every town and village in the country got its own extreme concrete makeover during this time. In the end, a few vestiges of the old settlement of Bohunice were kept – and if you get off the tram at Běloruská, and follow Havelkova street down the hill, you can discover some of them. I remember my surprise when, many years ago, I first stumbled upon the little chapel of St. Cyril and Methodius, surrounded by towering apartment blocks. It’s hard to imagine that the chapel was once the centerpiece of a village which was annihilated to make room for those towers. In fact, it’s easy to believe that it was done the other way around – that the paneláky came first, and the chapel was plopped in as a nice afterthought, a bit of attractive nostalgic scenery for the hard-working residents of those tower blocks to look down and rest their eyes on.

And in the end, I think that feeling might have been one of the main goals of the socialist city planners in the 1970s. They wanted to impose a new version of reality on the landscape, and to sweep away any reminders of a former, less enlightened way of life. Or, if they couldn’t entirely sweep those degenerate elements away, perhaps even better to deny them their proper space, to obscure their old function, to make them seem like aesthetic touches in a newer, more rational scheme.

It’s a bit unnerving that I can still feel the persuasive power of a totalitarian will which was imposed on this place 40 years ago – and that I can still sense its allure. Of course, it’s easy now to see how the world-dream which justified the destruction of old Bohunice, and the creation of the Housing Estate of Czechoslovak-Soviet Friendship, ended in a nightmare. How it led to a million other injustices besides what happened here, some of them a million times worse. And it’s easy to see how flawed that Communist dream was, how corrupt the sociopolitical order that sustained it was.

What’s harder to see – or rather, harder to accept – is that the products of monstrous, systemic injustice can sometimes be…well…pretty. When the sun sets on Bohunice’s south-facing slopes, the paneláky, coated these days in warm tangerine and lemon colors, glow with tranquility. And what was once a mudslide at the edge of Brno is now home to thousands of people – people who are growing up here, or growing old, whose bodies and imaginations are being formed and fed by this suburb of citrus light and evergreen shadows.

I’ve been one of these people, too. For three years, when I first moved to the city in 2006, I lived in a Bohunice panelák. And that’s the other big reason I’m happy that Bohunice comes first in my journey through Brno’s neighborhoods – because it was my first home in Brno. My own personal dreams of Czech life, and of Brno life, began to take shape here, among the concrete and juniper bushes. Since then, I’ve been drawn back here many times. Maybe I’m drawn here by a bit of nostalgia for that amazing period in my life. But also, I think, I’m drawn by these paths that weave life into strange geometries of history and ideology. As I walk through this neighborhood which has been so dramatically shaped by the great world movements of the past century – as I keep getting turned around in its mazes – the Campus above, and the sídliště below – I realize I’m also tracing multiple layers of my own footsteps, laid down imperceptibly over the years. And I’m reminded of how easy it is to get lost in a dream.

The best of Bohunice, briefly:

Most iconic view: The original 19th-century village chapel, with the monstrous 1980s “wall of paneláky” as a brutalist backdrop

Most ironic juxtaposition: A monument to the victims of Communism, just behind the Albert at Běloruská, in the middle of what was once the Housing Estate of Czechoslovak-Soviet Friendship.

Best street art: Bohunice’s spiffed-up suburban facades are disappointingly bare, but there are a few treasures, if you look hard. Honorable mention goes to this block-long Brno dragon on Rolnická street, surrounded by absurd slogans.

But my favorite is this little haiku-like poem stenciled at the bottom of a panelák near the Švermova tram stop, which reads, “Rychle rychle postavené krychle” [quickly, quickly built cubes]. It has been there at least since 2006, when I passed it every day (although Snoopy is a recent addition). The internet suggests this is an early work by the great Brno street artist Timo (I’m sure this won’t be the last time he’s mentioned in this column), which might be why it’s been preserved all these years.

Best hole-in-the-wall: If I ever get up the courage, I want to try Restaurace u Abána, which is wedged underneath Osová street where you might expect a drainage culvert instead. But since the place has no windows and only one door, which, in 6 years of watching, I’ve never seen anyone go in or out of, I’m too intimidated. Readers, if you’ve been there, I want to hear about it!

Instead, I can recommend either one of the restaurants in the old obchodní centra near the Běloruská or Švermová tram stops. Restaurace Kalinka (at Běloruská) serves Polička 11° and the typical pub food. Restaurace Kavkaz (at Švermová) serves a crisp Plzeň, and again the typical fare. Don’t get your hopes up for any nostalgic Communist-era charm from these places – they’ve been remodeled in recent years into clean, pleasant, family-friendly things. Most disappointing is Kalinka, since I remember when it was a claustrophobic Lord-of-the-Rings-themed acid-trip nightmare called Silmaril. I was only there once, but I seem to recall enjoying a soapy Gambrinus while staring at a styrofoam bas-relief of an orc. The only design element Kalinka has kept from Middle-earth is some bamboo in a pot near the entrance. The bamboo was once charmingly pointless, but now it blends smoothly into the vague theme of the whole pub, which might be described as “mall restroom with elements of dying jungle.” Oh well – the smažák is tasty, at least.

Most interesting architectural quirk / Most charming eyesore: The Rašino Ford dealership, with its pointy roof spikes mimicking (or mocking?) a similar design element on Ernst Wiesner’s 1920s functionalist crematorium across the highway. Whoever thought it would be a great idea to associate cars with burning coffins – I salute you.

Next month, I’m headed to Bosonohy, where no trams dare go. Does everyone there really walk around barefoot? I’ll find out. If you live in Bosonohy, or have any tips for me, get in touch.

More of Brno Neighborhoods: