Sunday evening saw the close of the ŠTETL FEST festival of Jewish Culture in Brno. Over 100 events were held over the four-day period, marking the biggest year of the multi-genre festival since its inception in 2022.

This year’s theme, ‘Jewish Trauma in Art From Kafka to Barbie’, sought to explore issues of generational trauma, the reflection of Jewish identity in artistic expression, and the relationship between society and the individual. While the majority of events were held in Czech, many were also translated into English, thanks to the work of an outstanding team of interpreters.

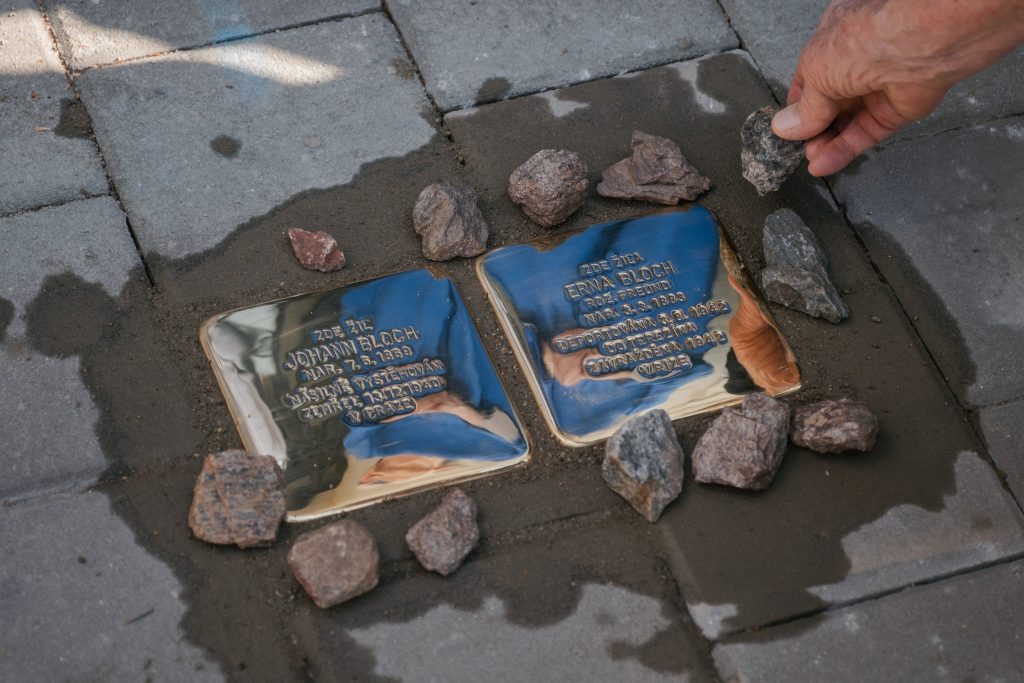

The festival began on a sombre note, with the laying of two Stolpersteine memorials for the Bloch and Ekstein families on Hlinky Street. The brass plates bearing the names of Johann and Erna Bloch, two Jewish residents who died during the Holocaust, will add to the nearly 300 other memorials in the city.

The idea for the Stolpersteine (translated literally as ‘stumbling stones’) began in 1992 with the German artist Gunter Demnig. Engraved by hand and placed at the location where the victims were last known to freely reside, the plates typically include the name, date of birth, and dates of death or deportation of the people they commemorate.

Since Demnig began his project, the concrete blocks have become a popular and grassroots means to commemorate victims of the Holocaust, funded and led by the research of local communities. Around 95,000 have been laid across Europe so far.

The Stolpersteine are intended to offer an alternative and de-centralised form of remembrance. They are designed, literally, to be stumbled upon, forcing observers to bow their heads to read their inscriptions. Their placement on the floor has been understood by some as deliberately provocative, suggestive of the desecration of Jewish cemeteries in Nazi Germany and making it possible for pedestrians to miss them entirely, or to step on them without noticing. Indeed, in 2018, local authorities in Munich decided to ban the laying of new Stolpersteine in the city.

The ceremony for the Bloch and Eksteins was attended by descendants of the families, as well as festival organiser Eva Yildizova, Rabbi Štěpán Menaše Kliment, and the chairman of the Brno Jewish Community, Jáchym Kanarek. In a short speech, Kanarek described the Bloch family as “part of the mosaic that the city is composed of” and thanked organisers for helping to remind Brno citizens of the darker parts of the city’s history. Stones were then placed around the two memorials, in accordance with Jewish custom.

The Bloch Family in Brno

The Blochs were a Jewish family who moved from the small town of Rousínov to Brno in the mid-19th century. While most of Brno’s industry was focused on textile production (hence the city’s contemporary nickname of ‘the Moravian Manchester’), founder Enoch made his name in the processing and production of leather goods. Four generations helped turn the business into one of the primary competitors in the leather market, employing 110 workers by 1919 and listed on the stock exchange in 1928.

In addition to their economic success, the Blochs were active participants in Brno’s civic and cultural life. After 1848, both Enoch and his sons Herman and Josef were prominent members of Brno’s nascent Jewish community. Herman’s children, Johann and Felix, had more distant relations with Judaism, but maintained close social ties with the community through the funding of several Jewish associations and charities.

Helen ‘Lene’ Bloch, Felix’s daughter, was the first woman of the family to attend a grammar school and went on to become a published poet and member of the Women’s League for Peace and Freedom in Brno. Lene’s sister-in-law, Annie Bloch, who married Felix’s son Erwin in 1925, served as secretary of the League for Peace and Freedom, gave lectures about the problem of statelessness, and worked as a member of the Committee of Jewish Women helping refugees.

By the time of the Nazi invasion, Johann Bloch was the co-owner of a large factory in Brno that employed hundreds and shipped to domestic and international markets. Following the invasion, the family initiated a distress sale to the rival Bat’a company and decided to emigrate, but were refused permission to leave. Johann Bloch later died in Prague in 1940 from heart complications while his wife, Erna Bloch, was deported to Theresienstadt and murdered in Riga in 1942. Other members of the Bloch family, such as Jonann’s brother Felix and his wife Luise, also perished in Chełmno and Łódž, respectively.

As part of the ‘Returns to Brno’ that ŠTETL helps facilitate, five descendants of the Bloch family participated in a discussion on Thursday morning. The event was chaired by Michal Doležel, a historian at the Brno City Museum, and Ines Koeltzsch, a cultural and social historian and expert in the history of Jewish and non-Jewish relations in Central and Eastern Europe. Koeltzsch, who works at the Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies and as a visiting professor at the Central European University (CEU) in Vienna, also delivered a lecture on the Bloch family in Brno on Thursday morning.

The various descendants of the Bloch family, who now live in the United States, France, and the UK, each spoke about their surprise and gratitude after being contacted about the plan for the event, but also the reticence that many of their elder relatives felt about ever returning to Brno, even to visit, after the war had ended.

Cheryl Bernstein, the great-granddaughter of Johann Bloch, shared her family’s difficulties in securing restitution of items stolen by the Nazis, and the long process she and her mother endured in order to finally reclaim four pieces of artwork and furniture which were left in Brno and Olomouc when the family fled Czechoslovakia. The discussion took place on Rybářská, where the following day a tour was organised of the old Bloch factory.

Elsewhere at ŠTETL FEST

Across the four days of the festival, the Memory of Nations Institute at Radnická hosted an exhibition displaying the childhood drawings of the artist and architect Petr Haimann, who as a young boy was deported to Theresienstadt with his family. The drawings offered a window into the imagination of a child confined to the cramped conditions of a ghetto; full of movement, wide landscapes and open spaces.

Alongside the drawings were displayed the results of a competition for children tasked with designing the final card in a deck of playing cards brought home by the young Haimann when he returned from Theresienstadt.

At the Villa Tugendhat, the British Rabbi Herschel Glück, founder and chair of the Muslim-Jewish Forum in the UK, took part in a discussion with Štěpán Menaše Kliment, Rabbi of the Jewish community in Brno. The conversation focused on the benefits of the Forum for “harmonious cohabitation” between Jews and Muslims, which Glück described as “not just a concept, but a reality”.

The Muslim-Jewish Forum, as well as the Arab-Jewish Forum which Glück also chairs, was established to deal with shared issues faced by Jewish and Muslim citizens in Britain, as well to create a space for respectful conversation about difficult issues. Using the example of his native Stamford Hill in North London, Glück emphasised the family values, care for the weak and dispossessed, and deep religiosity shared between observers of Islam and Judaism.

There was also acknowledgement, however, of the strain that the war in Gaza has put on communal relations and the current difficulties of engaging in a constructive manner because of the ongoing violence. An event in Czech was also held on Friday with Irena Kalhousová and Jakub Szántó about Israel-Palestine relations and the possibilities of a future peaceful settlement.

Elsewhere at the festival, the award-winning novelist and playwright Sara Blau took part in a discussion on Friday afternoon at Kino Art. Following a short reading from her debut novel ‘The Book of Creation’, in which Telma, the female protagonist, sculpts a golem statue to become her lover, Blau discussed her experience growing up as a young woman in a religious community in Israel and her desire to write about the experience of living as a ‘religious bachelorette’.

Saturday night saw the culmination of festivities at the Fait Gallery and the ‘Barbie Dream’ event, where, drenched in pink light, festival-goers enjoyed a night of live music and dj sets, stand-up comedy, and theatre performances. Other highlights included the Jewish Market hosted at the Old Town Hall on Sunday afternoon, and the ‘Jewish Identity in Photography’ exhibition at the Franz Kafka hospital. A full list of the events and photographs can be found on the ŠTETL FEST website and Facebook pages.