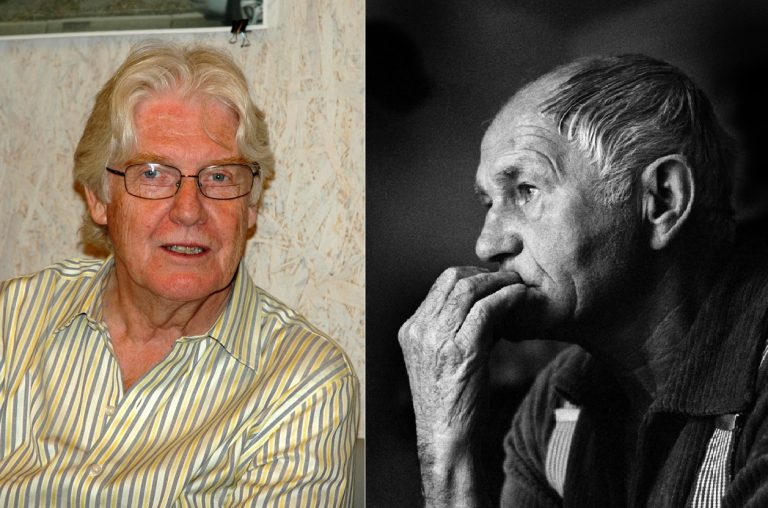

Bohumil Hrabal is often counted among the greatest Czech authors of the 20th century, and is one of Brno’s most celebrated sons. Our guest contributor Tanya Silverman interviewed his long-time translator Paul Wilson about the insights to be gleaned about the author from his most recent publication, “All My Cats” (2019), an English version of Hrabal’s 1986 memoir “Autičko”. Photo: Paul Wilson (left), Bohumil Hrabal (right). Credit: Jindrich Nosek, Hana Hamplova, via Wikimedia Commons CC-BY-SA-3.0

“Oh—and there were cats everywhere,” recounted Czech director Jiří Menzel about the cottage of his adored compatriot author, Bohumil Hrabal, located in Kersko. Menzel traveled to Kersko during the recording of the documentary CzechMate (2018) to revisit the Bohemian village where he shot his 1984 film adaptation of Hrabal’s The Snowdrop Festival (1978). Cats and Kersko stand at the core of Hrabal’s memoir All My Cats, a bittersweet account of how the prominent Brno-born Czech writer managed and mismanaged the many felines that inhabited his countryside abode.

The title All My Cats may come off as tender, however, upon reading, cruelty transpires when Hrabal’s inability to handle all of the beloved creatures prompts him to exterminate some of them. The book’s intimate illustrations of such scenes in first-person perspective are as vivid as the affectionate accounts of newborn kittens. Indeed, Hrabal’s inner monologue grows continuously fraught with guilt and remorse for his deeds. His thoughts sometimes metamorphose into hallucinations: “No matter where I slept, I’d wake up toward morning and a cloud would appear, a form of misty remorse that would gradually resolve itself into the shape of that cat, Máca, whose offspring I had treated in such bad faith that she couldn’t bear it and perished somewhere in the woods, over by Míček’s place” (p. 35).

Paul Wilson dealt with Hrabal’s conflicted contemplations as he translated the Czech Autičko (1986) into the English All My Cats (published in 2019). Autičko, a diminutive term for car, is also one of the memoir’s featured felines, whose name is retained as such in the English text. Hrabal originally wrote the memoir in 1983 as he was healing from a severe automobile accident, an event that acts as a prominent issue in All My Cats as well.

Wilson’s record of Hrabal translations includes I Served the King of England (1989) and Mr. Kafka (2015). All My Cats ended up being a more forgiving endeavor for Wilson than some of the short stories within Mr. Kafka. Specimens set in the Poldi steelworks in Kladno required Wilson to learn about the technical processes inherent to steelmaking. Unlike metallurgy, Czech cat terminology did not necessitate Wilson to consult native speakers with feline expertise.

Wilson visited Kersko with Hrabal’s biographer in preparation for this project. Here he provides some of his thoughts about translating All My Cats. The interview has been condensed.

You have translated several of Bohumil Hrabal’s works. What stood out to you about this particular piece of literature?

All My Cats is really a memoir, unlike Mr. Kafka—which are early short stories, mostly written in the 1950s, and I Served the King of England—a novel. It is Hrabal at his most personal, not so much concerned with the poetics of writing; there were fewer linguistic pyrotechnics; it is more about the truth and honesty of his experience with the cats. This is what readers seem to respond to, and why many of them have found it so moving, though parts of it are hard to read.

What similarities did you come across between All My Cats and the other Hrabal texts?

The work is still clearly written by Hrabal. He’s still interested in other people, and there are vivid cameos of others, like his neighbour who is worried about all the dead birds, or the young man who sympathizes with cows, or the woman who is a soccer fan. But the main focus is still him, and his response to killing the cats. There is also the theme of suicide, which appears in lot of his other work, including “Cain.”

During Late Communism, it was common for Czech city dwellers to acquire a second property in the country and escape into atomic existence. Hrabal’s attempts at arranging a little home in Kersko go awry with the cats. He cannot concentrate with them around. Would you say that this story acts as something of a microcosm for humans’ attempts at escape?

That’s for you to decide. I will say, though, that a more basic theme has to do with how we treat our fellow creatures. Hrabal ends up equating what he did to those cats with atrocities and murder, even mass murder. So if the book is in fact about escape, then more likely it’s about the impossibility of escaping our responsibility to all animate beings.

In the documentary CzechMate (2018), Jiří Menzel claims that what interests him about Hrabal’s writing is the ability to capture both beauty and sadness in his sentences. Would you agree with Menzel’s remark?

Yes. Hrabal even has a word for it: “Krasosmuteni.” You are never far, in Hrabal’s work, from the idea that life is essentially tragic.

Hrabal’s relationship with cats persists posthumously, in his literature as well as in the material world. The Hrabal Wall mural by Palmovka metro station in Prague features cats crawling around the author. Cat statues also adorn Hrabal’s gravesite. Can you comment on contributing to Hrabal’s legacy as an ailurophile (cat lover) for international audiences?

The association of Hrabal with cats is a particularly Czech phenomenon that has partly to do with Hrabal’s domestic popularity as a writer. It somehow softens the edges of some of the rougher rawer aspects of his writing. It makes him more human. It has also tipped into sentimentality and kitch. There’s a gift shop in Kersko that sells cute ceramic cats as souvenirs for people who make pilgrimages there. Given how some cat lovers here have responded to All My Cats, I don’t think there’s any danger of a similar cult starting here. You might even speculate that Hrabal wrote it to discourage his fans from having any illusions about his relationships to cats, and hence about him.