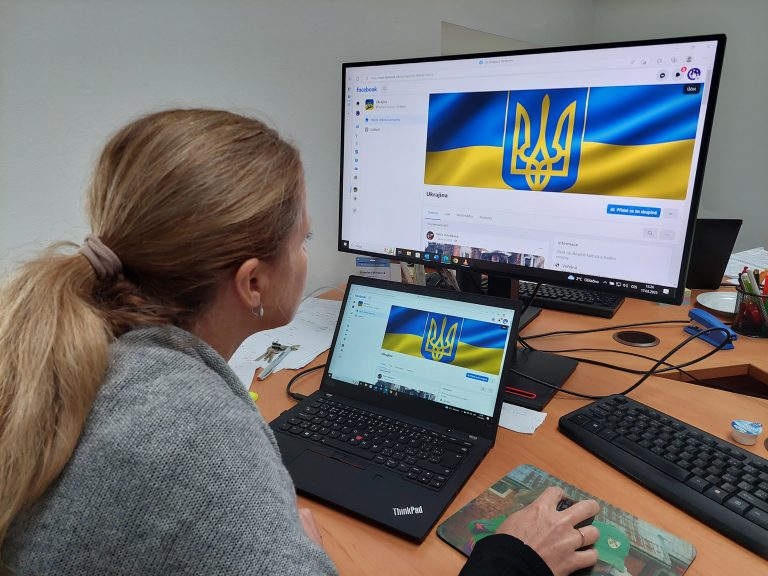

Overall willingness to engage in online discussions on social networks decreases during crises. Photo credit: SYRI Institute.

Brno, Feb 27 (BD) – The effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have brought polarisation in the opinions of users of Czech Facebook. Disinformation became very prominent during the pandemic, allowing conspiracy theories to thrive, and the war has since given already-active disinformation peddlers a new context to spread their influence further.

According to researchers Martina Novotná and Alena Macková from the National Institute For Research On Socioeconomic Impacts Of Diseases And Systemic Risks (SYRI), the willingness to join online discussions decreases during crises, while scepticism towards those with opposing opinions grows. Both crises have shown that what is happening within Czech social media is not significantly different from in other countries.

“It is positive that highly intolerant comments containing more serious forms of attacks such as racism, various other forms of discrimination or death threats appear in only about 8% of posts monitored,” said Novotná.

However, comments including milder versions of these attacks, such as the use of profanity or personal attacks, are becoming more and more common, totalling 59% of the posts from selected discussion threads appearing on Facebook pages of politicians or news sites.

“The fears that there would be an increase in indecent comments did not come true. The share of rude and intolerant comments in the Czech Facebook environment is in no way different from what is happening in the United States of America or, for example, in Brazil,” said Novotná.

Personal characteristics play an important role in the perception of what is acceptable and what crosses the line. More assertive participants in online discussions perceive profanity as an element of fun or response to rude comments.

“People who are less sure of their opinions are generally less active and tend to avoid conflict,” explained Novotná. “Therefore, they prefer not to participate in the debate and thus disappear from the public space, because intolerant comments are unanimously condemned by all debaters, who react to them by blocking or reporting inappropriate content.”

According to Macková, the fact that vulgar comments are often supported by arguments providing an explanation of opinions and attitudes is also positive.

“The data suggests that most of the time it’s not just shouting profanities and attacks. A more expressive way of argumentation can be used to emphasise arguments, to cope with opposing opinions, or is simply a standard form of communication for some debaters,” she said.

For both crisis periods, COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine, the discussion was characterised by an almost identical dynamic of vigorous exchange of views between the two main currents of opinion: The perceived polarity of opinion subsequently led to mutual misunderstanding and reluctance to listen to each other or discuss together. Willingness to engage in online discussions on social networks thus decreased, as the initial effort to correct and debunk myths was replaced by scepticism and feelings that opposing views made no sense.