Imagine Zdenda, a gay man living in a small village in South Moravia. In his town, there are no gay bars, no queer meet-up spots, and no safe spaces where he could openly meet potential partners. “If I wanted to look for someone here, I’d probably end up with gossip spreading through the whole village by the next day,” he laughs. Instead, Zdenda, like many other queer people in the Czech Republic, decides to turn to dating apps such as Grindr.

His story is definitely not unique. All across the Czech Republic, especially in smaller towns and rural areas, gay dating apps have become a lifeline – a way to connect, flirt, and sometimes even find love in places where offline opportunities are scarce. Even in Brno, with its relatively active LGBTQ+ community, many men say dating apps are still their main gateway to meeting new people. Dating sites and dating apps have thus played a crucial role in opening doors, not only for those who were too shy to meet people in the “offline world”, but also for people belonging to hidden or stigmatized groups, such as queer people.

Researchers have paid a lot of attention to dating apps as a phenomenon. We have evidence that there can be positive aspects of using the apps, but inappropriate or extensive use can lead to severe negative consequences. Despite this broad interest, much less attention has been given to so-called “gay dating apps” (GDAs) – dating apps used primarily by men who are attracted to men. Since more and more people are using these apps and rely on them to find other queer men, let’s look at some of the benefits and drawbacks of GDAs, and how they can impact the well-being and mental health of their users.

Why focus on queer users of dating apps?

One might assume that there are not many differences between gay and straight users of dating apps. However, unlike their straight counterparts, many gay men don’t have the same opportunities to meet potential partners in everyday life – there are fewer safe spaces, and risk of public discrimination is still very high, especially in Central and Eastern European countries such as the Czech Republic. For someone like Zdenda in South Moravia, that could be especially true, so instead of putting himself at risk, he can just log into an app and look for someone to meet in a relatively safe online space.

Gay dating apps can therefore provide a way to connect, explore identity, and find community. But they also come with unique risks. The focus on physical appearance and casual encounters can impact self-esteem, body image, and mental well-being in ways that are different from heterosexual users. This was shown in a 2019 study by Lauckner et al., in which the authors conducted interviews with 20 men who are attracted to men and who have been using GDAs. They frequently discussed instances of deception or “catfishing”, discrimination, racism and harassment. Another important factor is that the queer community, like many other minority groups, has a higher incidence of mental health problems than the majority. A recent Czech research report found that almost 40% of queer people were at high risk of depression, and a third struggled with severe anxiety. Therefore, shedding light on possible factors that contribute to the poor mental health of queer people is an important step to finding solutions and ways to improve the lives of queer people.

How do gay dating apps work?

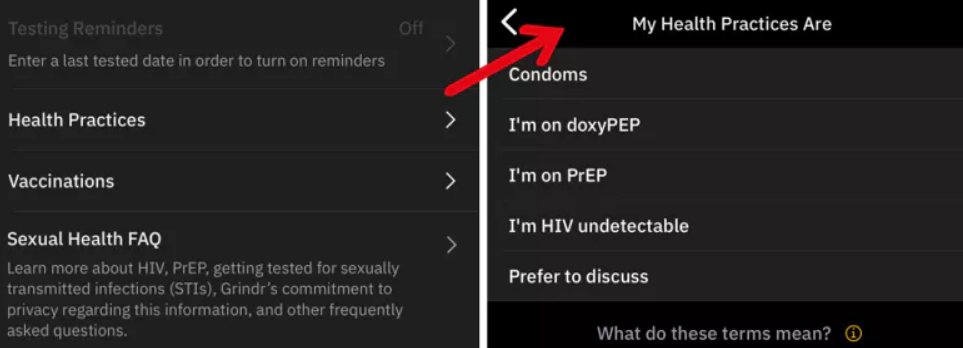

In order to understand the impact GDAs have on users, it’s important to understand how they work, because the features and resources they offer are what ultimately shape users’ experiences. Let’s focus on Grindr, which we could call the “flagship of GDAs”. Grindr was launched in 2009 and has played a pivotal role in how queer men connect online. Today, with over 14.5 million monthly users across 190 countries, Grindr has evolved into more than a dating app – it now offers important health information, supports LGBTQ+ causes, and promotes community events. The app provides a whole section called Community Resources – which includes not only important health information (for example about HIV testing or the usage of PrEP), but also an education section on other queer topics. For example, if Zdenda didn’t have other sources of information, he could easily find out through the app itself what it means when someone is non-binary, or if it is okay to ask a trans person about their birth name. Because of all this, Grindr has become a big part of how many queer people experience dating, connection, and identity in today’s digital age.

Let’s now take a closer look at how GDAs function, which may be different than you expect. “Classic” dating apps such as Tinder or Baddoo, which are designed primarily for straight people, are what we can call “swipe based”; the app shows you the people you might like, and by swiping left or right you can choose who you want to get to know better. The other person, however, has to “swipe” you back so that the connection is mutual. Here is where GDAs like Grindr are a little different.

Grindr enables users to view and message other nearby men in real time. Instead of swiping, the app presents profiles in a grid format, organized by how close they are to the user. The main difference from swipe-based dating apps is that anyone can message you if they’re close enough to your location. That means a lot of unwanted messages or even photos sent to you by people you don’t want to interact with. Let’s use the example of Zdenda again. Imagine he is trying to find someone his age on the app to meet someone new, but instead he sees messages popping up from men twice his age sending him inappropriate messages or even unsolicited explicit pictures. This would probably make Zdenda very uncomfortable. It might leave the whole experience of using the Grindr app tainted or even completely ruined. This is just one of the aspects of GDAs that lead to negative mental health impacts.

The not-so-glamorous side of gay dating apps

Gay dating apps may seem like a quick and easy way to connect with others, but many users report that their experiences aren’t always as fun or fulfilling as they hoped. While these platforms offer new ways to meet people, they can also bring a range of challenges, especially when it comes to mental health. From feelings of sexual objectification and emphasis on physical appearance to discrimination, GDAs can in some cases do more harm than good. For guys like Zdenda, who log on in the hope of meeting someone nearby, this reality can be especially discouraging. Even though the apps promise connection, they often deliver rejection or pressure instead.

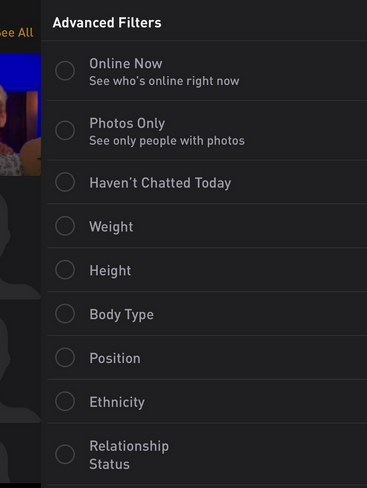

The first big problem that one might encounter on GDAs is sexual objectification – users treating other users solely as objects of sexual desire. Especially on Grindr, users can use all kinds of filters to limit who appears on their grid, including body type, or even height and weight, which can promote objectification. These filters encourage people to reduce others to specific physical traits, rather than seeing them as whole individuals. Profiles often emphasize torso photos or explicit preferences like “no fems” or “only fit guys,” which reinforces the idea that someone’s value lies mainly in their appearance or sexual appeal. It’s not hard to imagine how Zdenda might feel when faced with endless profiles asking for “perfect bodies”, or dismissing men who don’t fit a narrow mold. All of this can greatly impact how users feel and how they behave on the app.

There are also plenty of profiles without a picture of the face, that just show a part of the body. Other users might see this and be pressured to do the same. Over time, this can have a negative impact on self-esteem and body image. This was shown in a study by Filice et al., who surveyed Grindr users and found that the app affected their body image by stigmatizing their weight, encouraging them to compare their social status with peers, and by making them feel sexually objectified.

If we look back at Zdenda, he may start to feel pressured to edit his photos or hide parts of his identity just to fit in. What was supposed to be a tool for finding connections and potential partners can quickly become a space where he would feel judged, compared, or even invisible, which can be especially damaging for those who are already struggling with acceptance or self-confidence.

The focus on physical appearance goes hand in hand with another factor that can make it harder to find a potential partner: the emphasis on casual sex (or hookups) and sexting. A study by Yao et al. found that users felt deep dissatisfaction with the emphasis they felt online communities placed on casual sex. Imagine that Zdenda is trying to find his perfect long-term partner on a gay dating site, but once he finds someone who he likes and feels like he has a connection with, they start to talk about having sex with him and how they don’t want anything “serious”. This not only discourages many people from using GDAs to find a potential partner, but could also invoke feelings of loneliness and of “not fitting in” with the overly sexualized culture of GDAs.

Sadly, the drawbacks don’t stop there. People who try to find long-term relationships on these apps may even encounter discrimination from other users based on what they are looking for on the app. This may amplify the feeling of not fitting in even more and cause even more harm to someone who is not just looking for casual sex.

Last but not least, GDAs can sometimes lead to compulsive use, which can result in addiction. These apps are designed to get users hooked and keep them coming back to the app, even multiple times a day. There are also other factors that play a role in forming an addictive behaviour, such as the need for validation. Imagine if Zdenda had low self-esteem and didn’t meet queer people very often. He might make a profile on a GDA and get plenty of compliments and validation from other users, validation that he might not get anywhere else. And that’s where addictive behaviors might form – Zdenda might then continue using GDAs more and more often, leading to compulsive use, such as opening the app multiple times a day automatically, and even addiction.

Symptoms of addiction to dating apps are very similar to any other behavioral or substance addiction. A systematic review that explored what happened when people with behavioral addictions suddenly stopped these behaviors, found that the most prominent symptom of abstinence is craving. In the case of GDAs, this could manifest as an intense urge to go back to the app. If that craving is left unchecked, it can quickly spill over into negative consequences. For example, someone who suddenly stops using a dating app might feel intense loneliness or anxiety, leading them to find harmful ways of coping – like isolating themselves, engaging in negative self-talk, or even physically hurting themselves as a way to deal with overwhelming emotions. This is especially true if the app had become their main source of validation or connection. Therefore, it is really important to be aware of this issue and be vigilant when either you or someone you know might be exhibiting symptoms of addiction. One helpful step can be setting limits on app use or consciously taking breaks while finding alternative sources of connection – whether that’s reaching out to friends, exploring queer community events in Brno, or seeking professional support when the struggle feels overwhelming.

Is it really all that bad?

As we can see, there are plenty of reasons not to use GDAs. You might ask yourself, then, why would someone want to use them, when all you get are negative feelings? Surprisingly, or rather not so surprisingly, there are two sides to every coin, and GDAs can have many positive impacts on their users if they are used correctly.

For example, GDAs can provide great opportunities for meeting new people, especially for those with certain barriers to accessing potential partners in the “offline world”. In a 2019 study, the authors found that men who use GDAs mainly to find sexual partners report higher self-esteem and greater life satisfaction than those who use the apps for other reasons. This suggests that GDAs may work well for people seeking casual encounters. Of course, like any technology, they work best when expectations are realistic: they can be a great way to meet people and explore your identity, but may not always replace the deeper bonds that come from community or long-term relationships.

Anonymity can also play a big part when meeting new people as a queer person, especially when that person is not out yet (i.e. they haven’t shared their sexual identity openly with other people). A study published in 2013 found that anonymity in online spaces can help protect users from being outed, making it easier and safer for them to explore their identity and connect with potential partners.

Let’s look back at the example of Zdenda. Imagine him not being out yet and scared of running into someone he knows who might tell everyone in the village, which could cause him significant emotional distress. So instead of using his face as a profile picture, Zdenda can choose not to show his face until after he gets to know someone better and develops trust in them. In that way, GDAs can help control who you choose to disclose your identity to.

While gay dating apps are often associated with casual encounters, they can also offer a sense of connection and belonging – especially for those who lack access to LGBTQ+ spaces in real life. A study by Wu and Wang from 2018 found that for some, these platforms provide a digital gateway to community and help reduce feelings of isolation. This can be especially meaningful for queer people who feel isolated, either because they live in small towns like Zdenda, work in conservative environments, or simply don’t have easy access to queer spaces. Just knowing that there are other people like you nearby, even if you don’t meet them in person right away, can have a strong positive impact on mental health. GDAs create a kind of virtual community, where users can chat, share experiences, and feel seen and understood. Even short conversations or simple interactions can make users feel more connected and less alone. In Zdenda’s case, even if he doesn’t find the love of his life right away, just being able to talk to someone who shares similar experiences could be a huge source of comfort and support.

A double-edged sword

Gay dating apps like Grindr are powerful tools that have changed the way queer people connect, find partners, and navigate their identities. As we’ve seen, these platforms can come with serious downsides – including sexual objectification, pressure to fit into narrow beauty standards, and the risk of compulsive or addictive behavior. For some users, especially those looking for deeper emotional connections or long-term relationships, the culture of GDAs can feel alienating or even harmful.

At the same time, it would be unfair to dismiss these apps entirely. When used thoughtfully, and with awareness of their downsides, GDAs can provide a sense of belonging, safety and community, especially for those who might otherwise feel isolated. For queer people in rural areas or conservative environments, which is the case in many parts of the Czech Republic, these apps can offer a rare chance to meet others, explore their identity, and find support.

Like most technologies, GDAs are not inherently good or bad – their impact depends on how we use them, and how aware we are of both their promises and their downsides. The goal isn’t to reject these tools, but rather to understand them better and to create healthier, more inclusive digital spaces for everyone. And perhaps, somewhere between the chats and awkward first meetings, Zdenda and many others like him will find what they’ve been searching for all along – a genuine connection, understanding, and a sense of community.