A Neolithic settlement near Kutná Hora has been newly discovered by researchers from the Archaeological Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague. This settlement of the first farmers shows how people lived on Czech territory 7,000 years ago. It is unique in that no other settlements were built on the site over the following millennia, thanks to which the site has been perfectly preserved – including the floor plans of the four longhouses.

The lives of the first Neolithic people were not simple, and were closely connected with nature. They provided food for themselves by growing crops and raising livestock, but also by gathering and hunting. Although working in the fields without a plough and using only wooden tools seems almost unimaginable from today’s perspective, these communities were successful – within a few centuries they spread across most of Europe, superseding the original hunters and gatherers.

Prehistoric people settled in Dobřen near Kutná Hora, on the very edge of an area with sufficiently fertile soil and a suitable climate for prehistoric agriculture.

“At higher altitudes, i.e. more than 400 metres above sea level, settlements of this period rarely appear,” explained Daniel Pilař from the Institute of Archeology. “Apparently, thanks to this, the settlement was preserved and was not overlaid with younger buildings.”

Houses as shelter from cold and rain

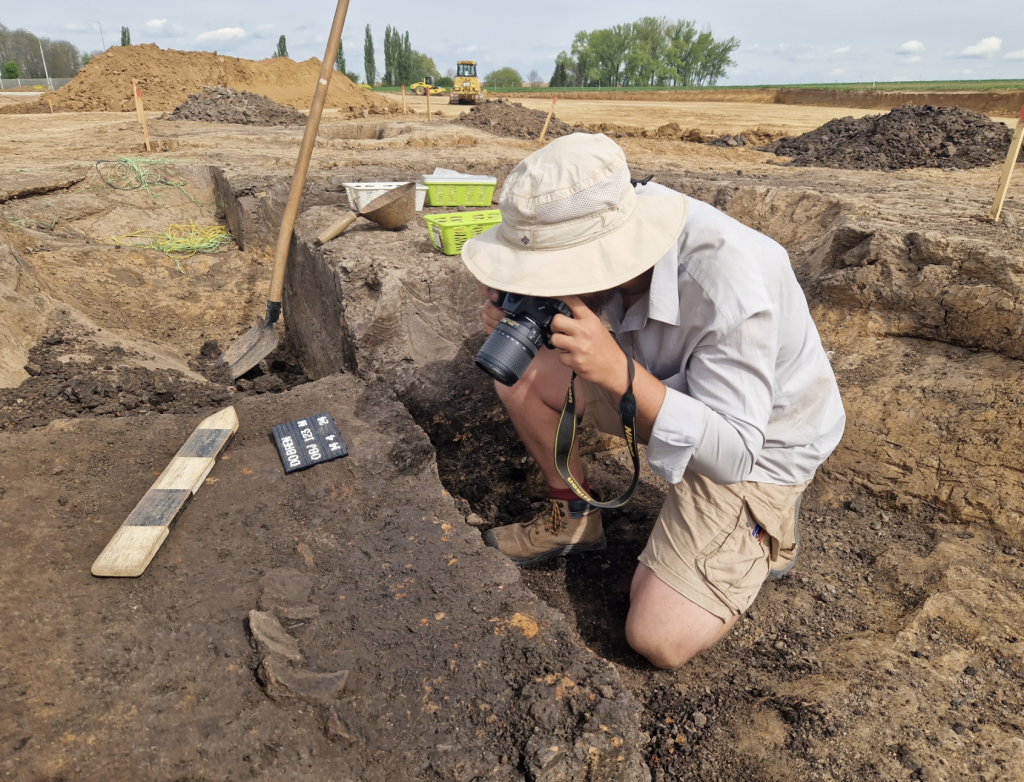

The hitherto unknown settlement from the Early Stone Age was built more than 7,000 years ago by communities of early farmers, who came to Czech territory from South-Eastern Europe. Archaeologists found floor plans of four longhouses – typical buildings of their time. Although the houses themselves have not survived, it is possible to find indications of their structure and layout via research.

“Houses used to be between 4 and 6 m wide and between 10 and 40 m long,” explained Pilař. “The columns are built most densely in the outer rows that formed the walls of the house, where they sometimes stood right next to each other. However, their inner rows have larger distances between them – usually more than a metre – so it was possible to move between them without any problems.”

The houses consisted of up to three parts. While the smallest houses had only one part and were around 10 metres long, in larger three-part houses one segment could be used for malting (this part usually has a floor) or as a central gathering place (with a more loose column structure).

Experts still debate whether Neolithic longhouses had multiple floors. Some buildings have part of the columns doubled, which could have served as a simple way to build a second floor. This phenomenon is always observed in only one part of the house.

Up to 40 people could have lived in the house, but estimates are usually much lower, from 10-20 people depending on the size of the house.

Regarding the use of houses, Pilař stressed that until recently, most daily activities took place outside the house, and people moved inside because of the cold or rain. In the summer, most activities took place outside, from food preparation to crafts, in part because it was simply dark in the houses. In winter, on the other hand, the houses offered shelter from the cold and rain. During these months, people could engage in some crafts inside the houses instead.

Waste pits as a window into everyday life

In addition to the houses, the surrounding pits were also an important discovery for the researchers; they were used to mine clay and were subsequently filled with waste, which gives a window into the everyday life of Neolithic people.

“With the help of modern analyses, archaeologists can currently investigate what the people of that time ate, how exactly they used their tools, and, last but not least, what the environment looked like 7,000 years ago,” explained Pilař.

The most common items to find in the pits were ceramics, used every day for cooking, serving, but also for storage. Moreover, this was a consumer product, which could easily be replaced with a new one when it broke. Sometimes used tools – flint blades, sharpened axes and stone grinders – also ended up in the pits.

“In addition to these common objects, we sometimes also find interesting objects illustrating everyday life: a charred clay wall that was ‘cleaned’ into the pit, or a clay oven for cooking food,” explained Pilař.

In the coming months and years, the experts will be intensively processing the data they collected in the field, such as by using radiocarbon and luminescence dating, as well as working traces on tools and plant genetics research. A wide team of experts from various fields will participate in the data processing.

The archaeologists will now hand over the site to construction workers, as the prehistoric settlement will be covered by a cow shed and an automatic milking machine, maintaining Dobřeň’s 7,000-year agricultural continuity.