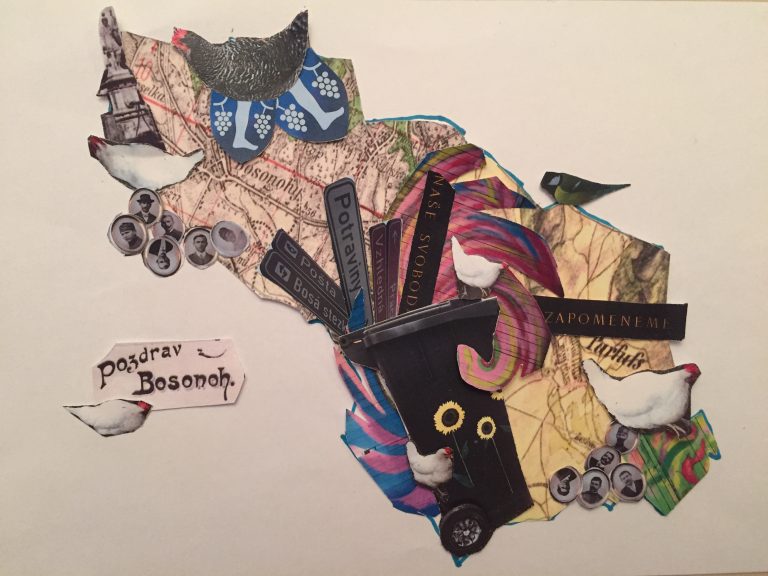

Work of art: Joe Lennon.

Part 2 – Bosonohy

Well, in one sense, I picked a bad time to start this column. I wanted to show you some strange and cool things to discover in Brno’s neighborhoods, and I wanted to encourage you to get out of your daily rut and explore new parts of the city. But now, we’re on total coronavirus lockdown for the foreseeable future, and so I must warn you to definitely NOT take this article as any sort of encouragement to walk around in strange places and touch pretty surfaces and spread this disease. Please stay firmly in your rut for now, and preferably in your own home.

But hey, I was proactive and stocked up on some journeys and photos before the quarantine. So while you’re trapped behind a screen, behind your front door, behind the Czech border, I can at least take you on a virtual tour of some nearby places which, as the viral curtain closes, might start to seem just as exotically out of reach as any Caribbean island, the Himalayas, or Boskovice. I hope that in a month or two, the worst danger will have passed, and we can hit the streets again during Brno’s best time of year. In the meantime, maybe it would help to imagine the city we want to see when we emerge from exile.

A few weeks ago, before the pandemic hit and the internet was still just for fun, the Brno cyberwebs were broken for a while with an endless stream of jokes and memes about Trump’s presidential jet taking a huge swerving detour to avoid flying over the city on its way to India. (Ah – remember that innocent time?) There was a snickering glee around the whole thing – we reveled in the thought that we had somehow repelled the world’s current asshole-in-chief. Sure, the official explanation was unfavorable wind patterns – but that didn’t keep brňáci from imagining all sorts of much funnier reasons why Trump’s plane had given the city a wide berth – most of them self-deprecating and self-aggrandizing at the same time. Like many of you probably did, I chuckled when I saw the first few memes, but as the posts kept coming, I started to roll my eyes – the jokes got predictable, it seemed that everyone was a bit too eager to show that Brno was going viral (too soon?), and it all started to feel rather forced – as if we were clinging to this minor blip on the world’s radar a bit too desperately.

But of course we were. Because Brno wouldn’t be Brno if it we didn’t breathe in desperation deeply like it was the purest alpine air. I think the main reason the Trump detour was so popular and compelling was because it was the epitome of a Brno thing. It showed (again) how powerfully unimportant our hometown is. It was a perfect excuse for us to perform (for a local audience, as usual) the paradox of our city’s identity – as a place that deserves attention and love for being ignored and unloved.

Brno is used to being Brno because of what it’s not. What it’s far from. What it’s at the edge of. What it will never be. Most importantly, it’s not Prague. Although these days, more and more, it’s also not Brussels, or Washington, or Beijing. But 150 years ago, it was mainly not Vienna. I love the title of the Moravian Gallery’s permanent exhibition, “Brno předměstí Vídně” (“Brno as a suburb of Vienna”). Again, in that short phrase, you have a perfect expression of Brno’s self-diagnosed Napoleon complex. That feeling of inadequacy at being only a distant, dusty suburb, and yet – that ambition to be seen as the coolest of the also-rans. That winking pride at mentioning our town in the same breath as the glittering capital of emperors and symphonies. (It even plays into the whole theme that Napoleon, the actual guy, staged his most famous victory just outside of town, in Brno’s own suburbs.)

And speaking of Brno’s suburbs brings me to this month’s neighborhood, the little village of Bosonohy. It’s actually not that far from the center of the city, as the DPMB trundles (in non-viral times) – just take the osmička to the end of the line, hop on a bus for a few stops, and you can be there in less than half an hour after leaving Hlavák. And yet, once you’re there, you can almost forget that you’re still in Brno. Although it’s (figuratively) just around the corner from the (literally) concrete (not-literally) jungle of Starý/Nový Lískovec, it is also (literally) just around a mountain from those high-rise suburbs. A thick-forested ridge wells up between Bosonohy and the rest of the city, editing out the views of paneláky and smokestacks, and giving the whole area an anonymous-Moravian-countryside feeling.

And honestly, if viewed as an anonymous Moravian village, Bosonohy is super-ultra-anonymous. Visually, almost everything about it seems designed to dampen any quirkiness or charm that a small village could try to claim. It fronts directly onto a busy, billboard-lined highway which used to be part of the Brno racing circuit in the 1970s and 80s. Now there are still speeding cars, but they aren’t being watched by anyone (including the police). Just uphill from the highway, there’s a quiet green ribbon of a náměstí that might have offered a pleasant vista of petite pastel houses in long rows – if it weren’t for a big white rectangular box of a school plopped down in the middle, blocking the view and ruining the feng shui. The rumpled terrain seems as haphazardly thrown together as the houses, and there’s an overall sense that this place is just squatting at the edge of a bigger town’s distracted consciousness. If Brno as a whole is a peripheral place, permanently marginal, always a suburb but never a center – then non-descript Bosonohy feels that much more marginal, a suburb of a suburb, a satellite captured and then forgotten.

But this area hasn’t always been on the edge of things. Bosonohy’s modern mediocrity hides some much older intrigue. If you want to get a feel for this place’s deeper past, head northwest from the náměstí and keep walking until the street turns into a gravel road between zahrádky, then a wide forest path. After about a kilometer and a half, if you swerve off the path to the left, skirt around a field, and scramble up toward the high ground, you’ll find yourself on a steep, rocky hill with wide views to the north and south. A little wooden sign at the top says “Hradisko 333 m n.m.” Archeologists have found pottery and copper tools here, as well as evidence of terraced fortifications, suggesting that about four or five thousand years ago, this was a small but bustling settlement. Standing on the mossy, pine-shaded bluff, watching the occasional car hum down the “Stará dalnice” below, it’s easy to imagine a more decentralized time, when hillforts like this were scattered over the landscape, and each one was its own scrappy seat of power. For generations of people, this minor bump of land was home, the center of their internal compass.

One of my favorite lines in any book comes early on in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. The main character, Marlow, is sailing down the Thames on his way to the Congo, where he hopes to find a primitive wildness he’s craved ever since he was a child staring at a map of Africa, fascinated by the big mysterious blank spot at the map’s center. As he drifts out to sea, he glances back at London’s ominous haze, and thinks about how this shining city was a savage and deadly marsh to the first foreigners who explored it. “And this also,” he says, “has been one of the dark places of the earth.”

Where’s the center, and where’s the periphery? Where do visions come into focus, and where do they blur? There was a time when the hills at the edges of Brno held civilization, and its river bottoms were a soggy swamp. And there’ll be a time (hopefully not soon) when Prague and Vienna and SKØG Urban Hub are giant firepits again. But in between, I think Brno will have to find some ways to be in the world because of what it is, and what it wants to be, not just because of what it’s not, or what it can’t be. An identity based on being unloved and unnoticed can’t hold up for long against plenty of sincere love and attention, which, despite what a few dedicated trolls on the Living in Brno Facebook group would have us think, the city is getting (and deserving) more of these days. Brno has been getting steadily richer, more diverse, and more popular. It’s becoming more of a destination in itself – and although this current crisis might dampen these trends a bit, I think they will probably continue post-corona. Maybe what will change – what needs to change – are our attitudes, and our perspective, about our position in the world. Just a few weeks ago, we were still getting a lot of mileage out of jokes about Brno’s second-rate, “fly-around” status. But suddenly, the joke is on the whole planet, and it’s not that funny anymore. All the glittering capitals are no-fly zones now, all of them are the dark places of the earth. But here, the sun is shining. All we have now, all we really are now, is here, in Brno, in this eerie warmth of early spring.

The best of Bosonohy, barely:

Most iconic view: If you stand at the top end of Hoštická street, you can look down the hill and see a long line of pretty (boring) village houses, then look the other way and see undulating fields backed by forests. Since you can’t actually go there now, you’re free to imagine what I saw when I stood there – a shimmer of deer high-tailing it across the fields.

Most ironic juxtaposition: On the náměstí there’s the typical Czech village war memorial – but this one feels especially sad. The original monument was built for those “fallen in the World War” (in the assumption that there would be only one), but below the original panel of names, they had to tack on two more marble slabs for the victims of what was, in retrospect, the inevitable sequel.

Best street art: There’s an important message sprayed on the blue bridge where Zájezdní street meets the highway: “Punk’s not death!!!” (see above). A bit more artistry went into the series of bright murals along Za Vodojemem street, especially this lovely lotus flower:

Best hole–in–the–wall: Hostinec U Čoupků, at the top end of the náměstí, has everything you could ask for from a village pub: a cavernous hall with big-screen TVs, Starobrno Medium as the default beer, lots of sepia photographs of the old days, and a waitress that has to be painstakingly summoned out of her own private dimension every time you want to order. I enjoyed it. You can too, when it reopens in – let’s hope April?

Most interesting object I found while walking: This piece of styrofoam which is shaped sort of like Minnesota:

Next month, if that giant asteroid carrying the coronavirus vaccine hasn’t crashed into Earth yet, I’ll take you on a virtual tour of tiny (and confusingly named) Brněnské Ivanovice. Until then, be well, friends.

Disclaimer: Opinions and views expressed in the text above are of the author. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.