Béla Tarr, the great Hungarian filmmaker, died a few days ago in a Budapest hotel at the age of 70, after a long illness. The news has passed almost quietly, as so often happens to those who never chased popularity, only truth. Tarr was the filmmaker of duration, of waiting, of slow ruin; he filmed the world not as a chain of events but as the gradual exhaustion of meaning. In his films, time does not console and does not redeem; it digs. It exposes what is left when ideologies have burnt out and words have lost their weight.

On hearing of his death, my instinct was to return to Werckmeister Harmonies, that unforgettable film I haven’t seen since its release in 2000. The memory of it was of something dark, radical, difficult. Yet revisiting it now is not an exercise in nostalgia; it is like standing in front of a mirror of the present, disconcertingly up to date. The film no longer feels like an abstract allegory, but like a precise diagnosis of the contemporary world. Rewatching Werckmeister Harmonies today means confronting our world with no illusions.

From order to managed disorder

Werckmeister Harmonies is not a film about chaos. It is a film about the moment in which disorder becomes normal, manageable, acceptable. The celebrated opening sequence of the “cosmic dance”, with János Valuska arranging drunk men as if they were planets, gives form to the classical idea of kosmos: a regulated, intelligible, harmonious world. It is the Enlightenment promise that the world can be understood, ordered, governed.

Yet that harmony is manifestly a performative construction: it works only as long as someone consents to believe in it. It is a narrated order, not a grounded one. This is also the condition of today’s international order, endlessly invoked while it is systematically violated. The war in Ukraine, Europe’s paralysis, China’s armed wait across the Taiwan Strait all show that “rules” hold only so long as they coincide with the prevailing balance of power.

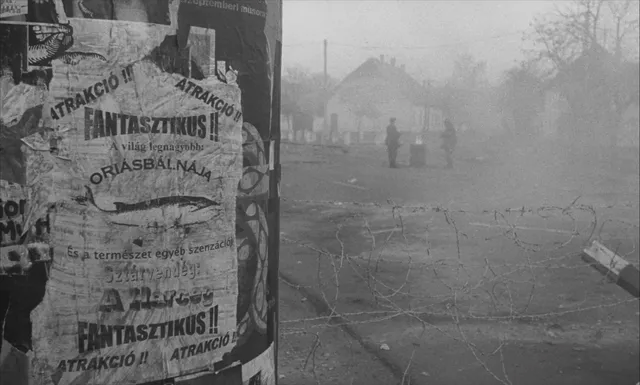

The whale and the banality of evil

When that harmony is no longer credible, the whale arrives. It is not evil, not an enemy. It is huge, mute, inert. It does nothing, yet it unsettles everything. It is the irruption of the real that can no longer be absorbed into symbols, the trauma that escapes moral language. Today that whale has very concrete faces: an unarmed woman killed by the police in Minneapolis; young Iranians repressed, imprisoned, executed; civilians reduced to figures in war reports. These are not anomalies, but structural mechanisms for selecting which bodies can be sacrificed.

Here the film speaks directly to Hannah Arendt and her notion of the “banality of evil”: evil does not need fanatics, only ordinary people who have stopped judging things for themselves. In Tarr’s town, no one is truly diabolical. No one acts out of deep conviction. It is precisely this normality that makes violence possible. It does not spring from hatred but from the suspension of thought.

The Prince, propaganda and organized brutality

The Prince, who never actually appears on screen, perfectly embodies this dynamic. He does not govern, does not administer, does not assume responsibility; he talks. He is power severed from consequence. Arendt understood that modern totalitarianism is rooted not only in repression, but in the erosion of spaces for thinking and the reduction of politics to slogans, identities and enemies. The Prince does not promise a better world; he promises a clearly identifiable enemy.

Today that function has been outsourced to permanent propaganda, platform populisms and the deliberate ambiguity of leaders who keep conflicts in a state of controlled tension. Truth is irrelevant; polarization is what counts. The hospital assault marks the point of no return. Violence does not strike at power but at the most vulnerable bodies. It is not revolution; it is the redistribution of brutality downwards. Tarr shows not Hobbes’s war of all against all, but the war of the many against those who cannot defend themselves. The Leviathan no longer shields us from violence; it organizes it, manages it, makes it functional.

Elites, neutrality and broken thinkers

Alongside the crowd, Tarr places the intellectual. György Eszter knows the harmony is false, knows the system is rigged, yet chooses not to disrupt its tuning. He accepts the prevailing temperament in order to avoid chaos. He is the figure of instrumental rationality described by Max Weber: concerned not with truth, but with what works. In this, the film issues a clear indictment of contemporary elites: knowing that the world is unjust is not the same as opposing it. Neutrality is not innocent.

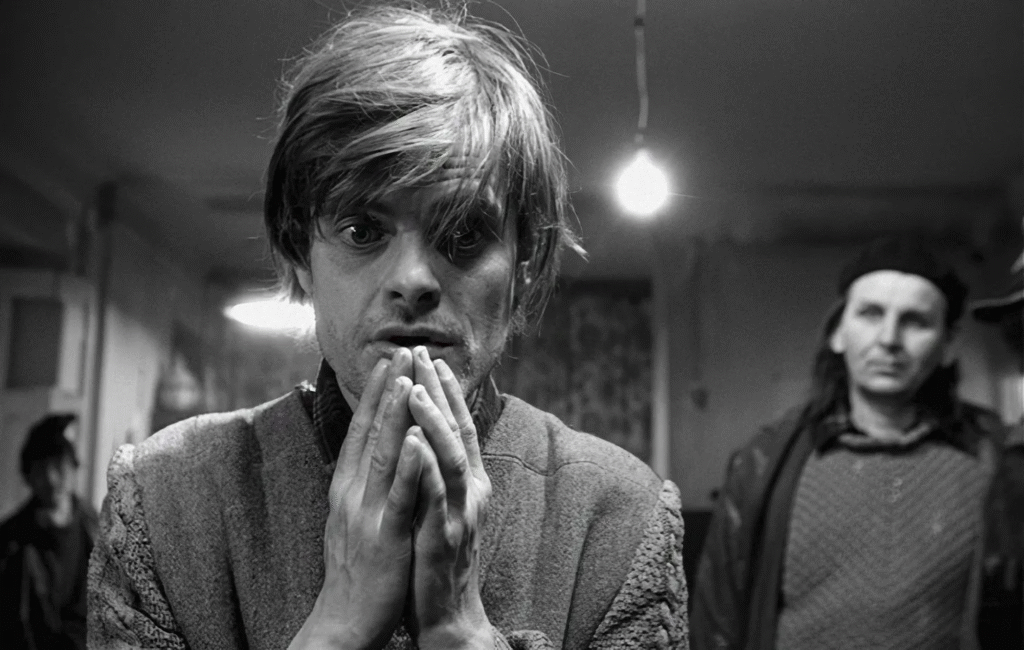

János Valuska is the anomaly the system cannot absorb. He does not shout, simplify or designate enemies. Precisely for this, he must be broken. As in Arendt’s work, the person who really thinks becomes unfit for the world. His final breakdown is not a private madness, but the symptom of a society that no longer tolerates non-functional thought. In a reality built on polarization, complexity itself becomes pathological.

The naked whale and the end of consolatory metaphors

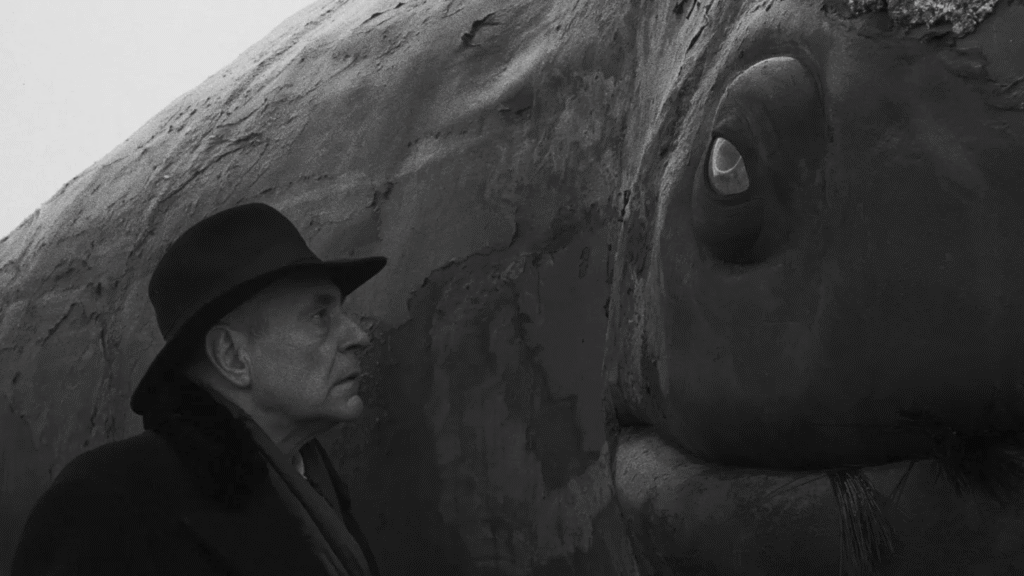

When the whale is finally uncovered, it is neither removed nor erased. It is stripped from its casing, overturned, exposed. It is no longer spectacle, no longer collective fetish, but bare body: matter, enigma. Eszter approaches, stops, lingers over one of its enormous eyes. There is no explanation, no redemption, no final word—only a gaze that arrives too late. The whale remains there, naked, without a frame and without a story: the real without mediation.

At this point Werckmeister Harmonies stops functioning as metaphor and becomes a warning. A warning against the illusion that evil is always spectacular, external, easily recognizable. A warning against the belief that dismantling the monster is enough to heal the world. Even after seeing it, it is still possible to choose to change nothing.

To rewatch the film today—after more than 20 years, and in light of what is happening around us—means facing an uncomfortable truth. The wars followed at a distance, the repression skimmed over in passing, the ambiguities of power excused in the name of “stability”: they all obey the same logic as Tarr’s village. Disorder no longer shocks us, so long as it does not reach us personally.

For this reason Werckmeister Harmonies ought to be seen again today, collectively, with a critical, unsentimental gaze. Not to extract answers, but to measure our ability—or inability—to recognize when the harmony we defend is nothing more than an elegant form of resignation.

Béla Tarr does not ask for hope. He asks us to look, to the very end, without reassuring allegories. If that gaze makes us uncomfortable, it is because the film no longer speaks of a possible world, but of our own. It stands as a warning—for everyone. The task now is to watch it with eyes that are critical, lucid and awake.