It has been more than a month since the elections to the Chamber of Deputies (Poslanecká sněmovna) of the Czech Parliament. The elections were won by the ANO movement, and its leader Andrej Babiš is currently engaged in coalition talks with Freedom and Direct Democracy (SPD) and the Motorists. In this article, we will take a look at the available data and consider whether Czech society is becoming increasingly politically divided.

The winners

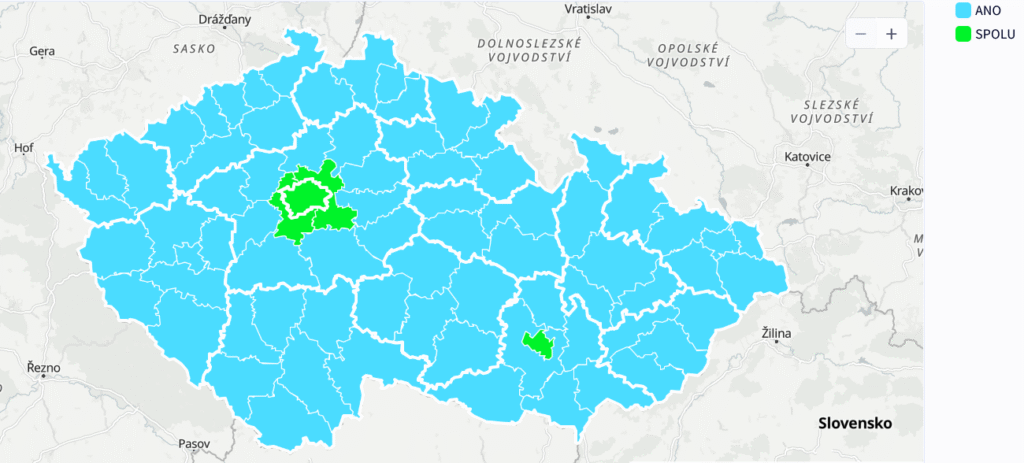

As already mentioned, the clear winners in the elections were the ANO movement, which received more than 1.9 million votes, the highest in its history, and also the highest number of votes for one party in the history of Czech elections. Thanks to this victory, ANO secured 80 out of 200 seats. This success can be attributed to the active campaign led by Babiš, who performed strongly in economically disadvantaged and more remote regions, managing to draw voters from Tomio Okamura’s SPD and convincing many undecided voters to cast their ballots for him. His victory was also driven by a strong showing among pensioners, the unemployed, and people with lower levels of education. His landslide victory is clearly visible on the election map, where the light blue of ANO covers almost the entire country, with the exception of Prague, Brno, and their surrounding districts.

Another winner of this election was the Motorists, who managed to climb over the required 5% threshold for the first time. Throughout most of 2025, polls showed them hovering around 5%. The party was also affected by controversies surrounding its most prominent figure, Filip Turek. Nevertheless, it ultimately received nearly 6.7% of the vote, securing 13 seats. The party’s main campaign slogan, “Oust Fiala, control Babiš“, clearly indicated its preferred post-election partners. Thanks to their result, the Motorists are now finalizing coalition negotiations with Babiš. They drew much of their support from undecided voters and supporters of smaller parties. Unlike ANO, their voter base spanned all age groups, with particularly strong support among young workers and students.

The only winners from the so-called “government camp” were the Pirates. Although the party had been part of the governing coalition after the 2021 elections, they decided to leave the coalition in autumn 2024 after Prime Minister Fiala dismissed the Pirate leader Ivan Bartoš from the government. Following this dismissal, polls showed the Pirates at around just 5–6% support. However, the party managed to regain popularity and improve its standing, ultimately receiving nearly 9% of the vote and securing 18 seats, a significant increase from their previous four seats. Thanks to preferential voting, 14 of their 18 new MPs will be women. The Pirates’ core voter base consisted mainly of young people, students, and individuals with higher education in cities such as Prague and Brno.

The losers

The outcome of this year’s election was a significant blow for SPOLU. This three-party coalition won the previous parliamentary elections in 2021, narrowly defeating ANO with 27.79% of the vote, compared to ANO’s 27.12%. This year, however, SPOLU managed to convince only 23.36% of voters to cast their ballot for the coalition. Although SPOLU lost only around 180,000 voters, the main reasons for its defeat were ANO’s exceptionally strong performance and the much lower number of wasted votes compared to 2021. While more than one million votes were wasted in 2021, this year it was only about half that. As a result, even without a dramatic drop in its own support, SPOLU lost 19 seats, to the benefit of ANO and the Motorists. Their core voter base this year consisted of businessmen, small business owners, students, and people with higher levels of education. The coalition performed best in urban centres, winning in Prague, Brno, and their surrounding districts.

STAN, SPOLU’s coalition partner, also performed worse than in 2021. Back then, they ran in a coalition with the Pirates and received around 15.6% of the vote. However, due to preferential voting, most of the seats went to STAN, leaving the Pirates with only four of the coalition’s 37 mandates. In this election, STAN ran without the Pirates, who took a substantial portion of STAN’s 2021 voter base with them. As a result, STAN received only 11.23% of the vote and lost a third of its seats, dropping from 33 to 22 mandates. Despite this significant decline, it is still STAN’s best ever standalone result, and a great improvement from 2017, when the party took just 5.18% to win six seats in the Chamber of Deputies. STAN thus continues to strengthen its position on the Czech political scene. This year, it was the most popular party among students and younger people with higher education, and also succeeded in attracting a notable share of former SPOLU voters from 2021.

The outcome of the October elections was certainly not a cause for celebration for SPD. The party received only around 7.8% of the vote, a decline from the 9.56% it won in 2021. This resulted in the loss of a quarter of its seats, dropping from 20 to 15. However, because SPD placed several members of smaller allied parties on its candidate lists—and positioned many of them at the top in various regions—SPD itself will hold only 10 of those 15 seats, with the remaining mandates going to prominent members of these smaller parties.Despite this significant loss, SPD was invited by the victorious ANO movement to take part in coalition negotiations, and it now appears highly likely that SPD will serve as part of the future coalition government with ANO and the Motorists. In this election, SPD’s core voters were primarily pensioners, the unemployed, and older residents of rural areas.

A tale of “two Czechias”

The results of this election indicate a trend already pointed out by several commentators: an increasingly pronounced division across Czech voters and society into the so-called “Czechia A” and “Czechia B“. This divide reflects two groups differentiated primarily by income, education, and their level of trust in the current political and economic system.

Czechia A consists of urban, higher-earning individuals with higher levels of education, whose political orientation tends to be more liberal or progressive, and ranging from centre-right to centre-left on economic issues. This group primarily votes for the SPOLU coalition, STAN, and the Pirate Party. Their voting patterns correspond to the data presented earlier. Socio-economically, this group was far less affected by the economic slowdown following the Covid-19 pandemic. This is reflected in real wage developments. In Prague, real wages (wages adjusted for inflation, indicating the purchasing power of workers) increased by CZK 1,700 between 2019 and 2025, while in all other regions (except South Moravia), they declined. As a result, citizens in “Czechia A” tend to focus less on basic economic concerns and more on issues such as security, foreign policy toward Ukraine, or maintaining a balanced budget.

The second group, labeled “Czechia B”, delivered a decisive victory to its main political representative, the ANO movement. Voters in this group tend to come from less developed regions and generally have lower levels of education and lower wages. This group is characterized by more conservative cultural views, left-leaning preferences on economic issues, and ongoing economic insecurity. They continue to feel the impact of the post-Covid economic slowdown. As noted above, their real wages declined between 2019 and 2025. In the Liberec region, for instance, real wages dropped by an average of CZK 2,800, and unsurprisingly, ANO dominated the vote there with 34%. For this group, basic economic needs such as housing, healthcare, and pensions were clearly reflected among their stated policy priorities.

A Turning Point for Czech Politics?

These findings suggest implications not only for party competition, but also for the ability of future governments to govern effectively. As the electoral map becomes increasingly polarized, forming policies that speak both to urban, well-educated voters and to citizens in economically struggling regions will become more difficult. The anticipated ANO–Motorists–SPD coalition will face strong pressure to deliver tangible improvements for voters in “Czechia B”, while at the same time navigating the expectations of more moderate or economically liberal segments of the electorate.

Unless policymakers address the underlying drivers of inequality, including regional disparities and declining purchasing power, the gap between these two groups is likely to widen even further. The 2025 elections thus serve not only as a snapshot of shifting political preferences, but as a warning sign of a society increasingly split along socio-economic, educational and geographical lines, with potentially lasting consequences for Czech democracy.