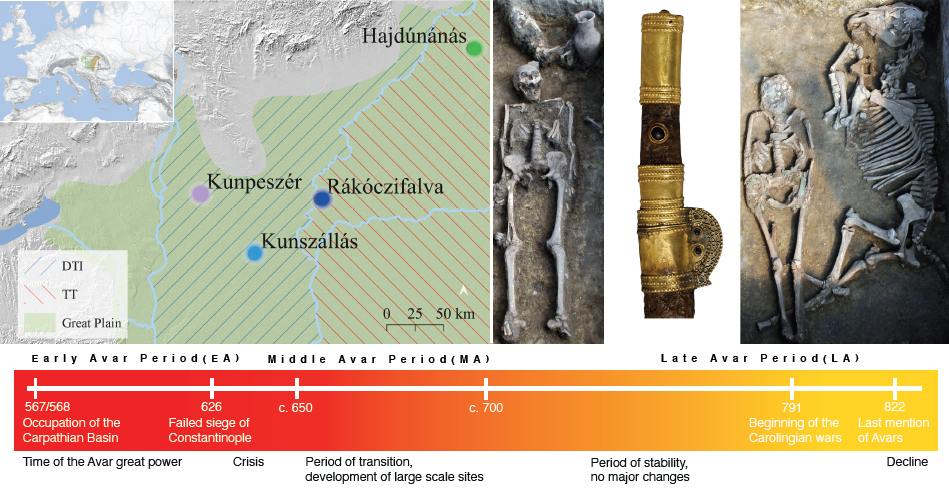

The prestigious journal Nature has published a new study revealing details of the long-vanished Avar society, which ruled central and eastern Europe from the 6th to the 9th century AD. The multidisciplinary research team of geneticists, archaeologists, anthropologists, and historians, led by Zuzana Hofmanova from the Institute of Archeology and Museology at the Masaryk University Faculty of Arts and the Max Planck Institute, used detailed genetic and archaeological analysis of samples of all available human skeletal remains from four Avar burial sites in present-day Hungary to study the family ties and societal structure of these ancient communities.

The team, funded by the European Research Council (ERC), brought together experts from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (Leipzig, Germany), the Institute of Archaeological Sciences of Loránd Eötvös University (Budapest, Hungary), the Curt Engelhorn Center for Archaeometry (Mannheim, Germany), the Institute for Austrian Historical Research at the University of Vienna (Austria), and the Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, USA).

The Avars came to Europe from East Asia, and ruled much of East Central Europe from the 6th to the 9th century AD, when they were conquered by the Magyars.

Although not as well-known as their predecessors, the Huns, they played a decisive role in the region, mainly because of their relationship with the Slavs. They left one of the richest archaeological legacies in their burial grounds, including about 100,000 archaeologically uncovered graves. Four sites which have been completely archaeologically explored were used in the study.

Thanks to DNA from 424 individuals collected in the burial sites, scientists managed to reconstruct a deep genetically documented family tree, which spanned nine generations and about 250 years.

“We found that of the 424 individuals, about 300 of them had some close relative buried in the same burial ground,” explained Hofmanová. “This surprisingly high level of kinship allowed us to reconstruct extensive family trees, and the nine-generation one literally took our breath away.”

“Historical knowledge about the Avars was left to us only by their enemies, mainly the Byzantines and the Franks, so these results provide insight into the internal organisation of their clans, while women were very little represented in historical sources. We only know of three casual mentions, so knowledge about their lives is practically non-existent,” she said.

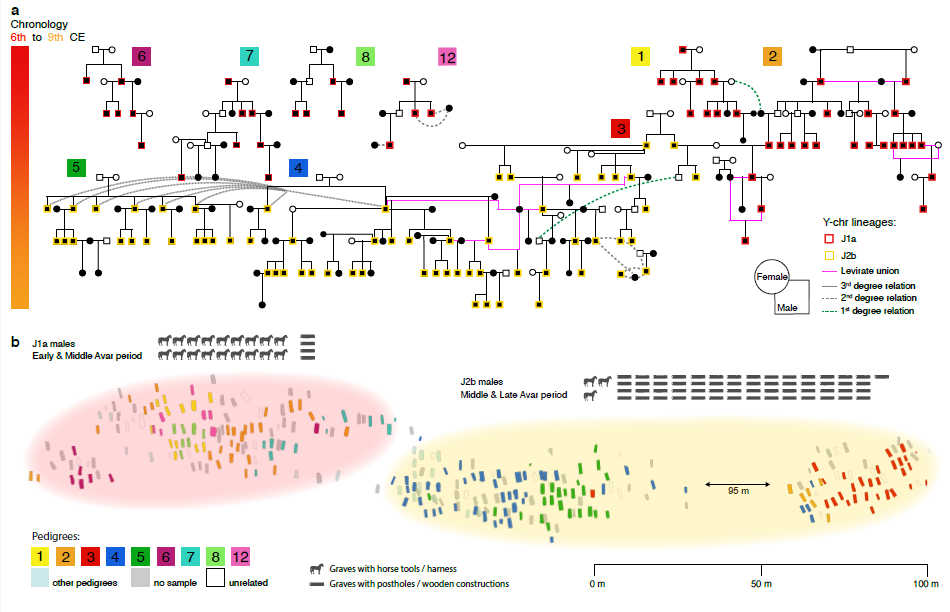

The genealogies revealed that the communities followed a strict patrilineal system. However, according to the new genetic data, women played a key role in the social cohesion of Avar society, connecting individual groups and clans through marriage, after which they left their original native community. Women thus provided links between different communities.

“It is also interesting that it was common to have multiple reproductive partners during one’s lifetime,” continued Hofmanová. “More independent examples also show that these communities practised so-called levirate unions. Their essence lies in the fact that male relatives – siblings or father and son – have an offspring with the same woman, who is not biologically related to them.”

Such practices are a historically and ethnologically documented custom of Asian nomadic societies, and have an important role in succession in the community, protection of children, and maintenance of political bonds between groups. This finding outlines that the Avars kept these steppe traditions for centuries after settling in Europe.

“In these communities, intermarriage even by distant relatives was completely avoided, suggesting that Avar society maintained a detailed memory of their ancestors and knew who was whose biological relatives for generations,” said Guido Alberto Gnecchi-Ruscone, a researcher at MUNI and part of the research team.

At one of the largest investigated sites, a sudden change was detected in the second half of the 7th century. One paternal line was replaced by another, and at the same time, there was a change in eating habits and burial.

The research team said that this exchange of community was probably connected to larger political changes in the region, and would have been genetically invisible if the study had not been so detailed. This shows that the same genetic ancestry can mask the replacement of entire communities, which has implications for future archaeological and genetic research.

“Interestingly, the original and new paternal lines were still genetically linked through offspring with the same woman,” concluded Hofmanová. “These analyses also reveal individual stories and relationships between individuals: fathers buried, surrounded by their sons and their partners, and daughters who disappear from communities around the age of 18.”

The findings of the research are unique, especially for the magnitude of the genetic research behind it. The importance of this study caught the attention of one of the most prestigious scientific journals in the world, Nature, which has now published the results.