The aim of the research was to discover what happened to the remains of those political prisoners who were not buried at the Dablice cemetery or the burial site in Motol, both in Prague. Photo credit: Freepik.

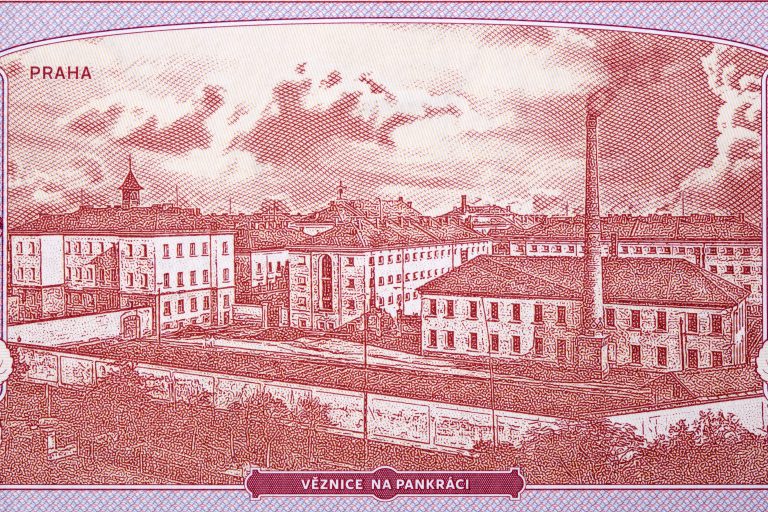

Prague, June 12 (CTK) – Scientists have uncovered a burial site at the Prague-Pankrac prison, containing the cremated remains of more than 80 political prisoners who died between 1948 and 1965, said experts Ales Kyr, Alena Simankova and Jan Marik at a press conference today, presenting the results of their archaeological research.

The people buried there were executed opponents of the regime from various prisons in Czechoslovakia and people who died in the Pankrac prison hospital, as well as soldiers who had participated in the anti-communist resistance.

Kyr, a historian of the Prison Service, said the scientists had found the remains of burnt bones in the ground at the site of the former execution place where prisoners were executed between 1947 and 1954.

“The area was then cleared and the gallows from both execution places were removed. After that, the site was not used until 1992, when a commemorative place was established there,” Kyr told reporters.

The soil survey was carried out there last October and archaeologists found remnants of organic material in the soil. Subsequent analysis determined that those were fragments of burnt bones.

“We can assume that these are the remains of people whose urns were emptied here,” said Marik, the director of the Institute of Archaeology at the Czech Academy of Sciences.

Scientists do not have an exact list of the victims buried at the site, and are relying on historical records to determine whose remains might be at the Pankrac burial site.

Simankova, from the National Archives of the Czech Republic, noted that the remains of journalist Zavis Kalandra, who was sentenced to death along with democratic politician Milada Horakova and executed in June 1950, have not yet been found.

“His urn was undoubtedly brought to Pankrac. But we can only say maybe. And from the remains that have been found, you cannot determine specific people,” she added.

The aim of the project was to discover what happened to the remains of those political prisoners who were not buried at the Dablice cemetery or the burial site in Motol, both in Prague.

First, the researchers had to find cremation numbers, to prove the deceased was really cremated. “Then, we had to find out whether or not the urn was given to relatives or family,” Kyr explained. However, he said, the remains were rarely handed over to the relatives. Most of the urns were taken to the Pankrac prison, where they were stored.

Some of the urns were taken to Motol in 1965, but the rest have not been found. In some cases, scientists have found a record of the urn’s destruction. From archival documents, they found out that in 1961, the interior minister issued an order that the remains from the urns be mixed with the soil.

“Why exactly some of the urns were destroyed and some kept until 1965, when they were brought to Motol, is not known,” Simankova said.